"Severance" and the Departmentalization of Compartmentalization

The weirdest show on TV is also the most resonant.

Warning: Spoilers for the season finale of “Severance” contained herein.

I held off on writing about Apple TV+’s new series “Severance,” because I wanted to get to the season finale before weighing in and also because, by Episode 3, I was kind of freaking out. I have to imagine anyone who has spent time in a mid-to-large corporate office might feel the same way.

If you haven’t seen “Severance,” it’s set in the headquarters of Lumon, a company that — well, it’s never entirely clear what Lumon does. Something cutting edge and biotechnical, but the four employees of the Macrodata Refinement Division aren’t sure what the product is, in part because they are the product. Like selected Lumon employees, they have agreed to undergo an operation that implants a device in their brains that completely cuts work life off from outside life. Once the widget is switched on, employees are “born” into their job with no memories or knowledge of their homes, families, or past. Once they leave the office for the day, they have no memories of what happened at work. They have been cleaved in two, citizen and worker bee, one free to live as he or she chooses and the other wholly dedicated to what they do at their desk because that’s all they know. It’s brilliant, it’s efficient, and it’s terrifying.

It’s certainly frightening to Helly R. (Britt Lower, above), who in the opening episode wakes up from her operation with an immediate case of the lemmeouttaheres. She joins the Macrodata Refinement Division as a replacement for Petey, an employee who just isn’t … there anymore. No one knows why, but her coworkers, brusque Dylan (Zach Cherry), timid Irving (John Turturro), and Helly’s nervous, newly promoted boss Mark (Adam Scott), smile as if nothing’s amiss, and their supervisor, Mr. Milchick (a superb Trammell Tillman) has a grin that’s even bigger and more fraudulent. To keep troop morale up, Milchick regularly appears with vaguely surreal rewards: a melon buffet, or a “Five-Minute Music Dance Experience.”

If an employee does something wrong, he or she is sent to the Break Room. You don’t want to go to the Break Room. It’s not the kind of break you’re thinking of.

When you’re at work here, you only know your “Innie,” your work persona. At home, you’re your “Outie.” The two have never met. As created by Dan Erickson and directed by Aoife McArdle and Ben Stiller (yes, that Ben Stiller), “Severance” takes the compartmentalization we employ as citizens of a modern society — the code-switching, the who we are depending on where we are and who we’re with — and literalizes it as an Orwellian dystopia that looks just like today.

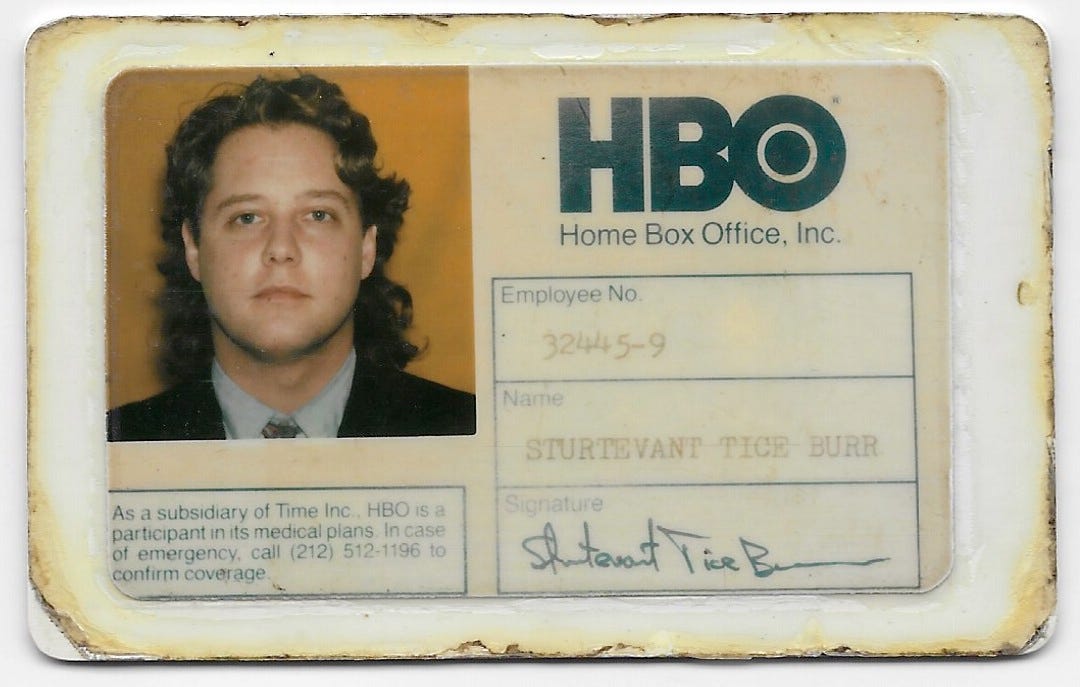

Or even yesterday. Why did I get the chills while watching this show? Because the long white hallways of Lumon, the corners around which are simply more corners, the office spaces that are functional and poorly carpeted veal pens all felt like a vivid flashback to my first post-college job, in the research department of Home Box Office in New York City during the 1980s. HBO was still working out of the sixth floor of the Time Life Building when I started in 1982 — it wouldn’t move to its own headquarters at 1100 Sixth Avenue for another few years — and one ventured to the other floors at one’s risk, never knowing what was behind those infinite corridors of doors. If you stayed at work late and had to wait for the night elevators to come — it could take a half hour or more, since they stopped at every one of the 48 floors — you could hear the building sighing and talking to itself. It was like something out of “Brazil.”

My job was analyzing Nielsen viewership data with the eye of a recent graduate in Film Studies, the thinking being that since HBO was just movies and boxing at that point, they might as well hire someone who knew about one of those things to decipher what people watched and why. We didn’t have melon parties or dance-offs, since that kind of Human Resources creepiness wasn’t invented until the 1990s. It was pretty much drone work. I might have enjoyed it more if I’d been severed. I probably would have been better at it.

Until the season finale, the only character in “Severance” whose outside life — whose Outie — we see is Mark, who’s played by Scott with a troubled set of pursed lips beneath his large, liquid eyes. Innie Mark doesn’t know that Outie Mark lost his wife to a car accident a few years back and has been in a bad way with booze and depression ever since (although why Innie Mark never seems to feel Outie Mark’s hangovers is an unresolved question). The arrival of Helly R. at work and the appearance of the distraught Petey (Yul Vasquez) in the outside world is enough to turn Mark into our Winston Smith, our Bernard Marx, our all-purpose Charlton Heston. Doubt creeps in. Discoveries are made. Plans are laid.

There are series cliffhangers that make a viewer feel cheated, but this wasn’t one of them. “Severance,” Season One, went out on a high of revelations and realizations — both in the characters and among viewers — that effectively kicked this office-bound show into a rougher and far more suspenseful orbit. A more resonant one, too, because we were forced to imagine: What would happen if the walls of the department of compartmentalization came down and our Work Self was suddenly asked to correlate to our Home Self, our “real” self? Would they recognize each other? Would one be more ethical or more naive or meaner than the other? Would one be more capable of feeling? More than once watching this show, I was reminded of how I’ve come home from my many employments over the years, loosened my real or metaphorical necktie, and become another person — a husband, a father, my self. And I’m reminded, too, that I work from home now, as so many people do, and that I erect compartment walls there at my peril.

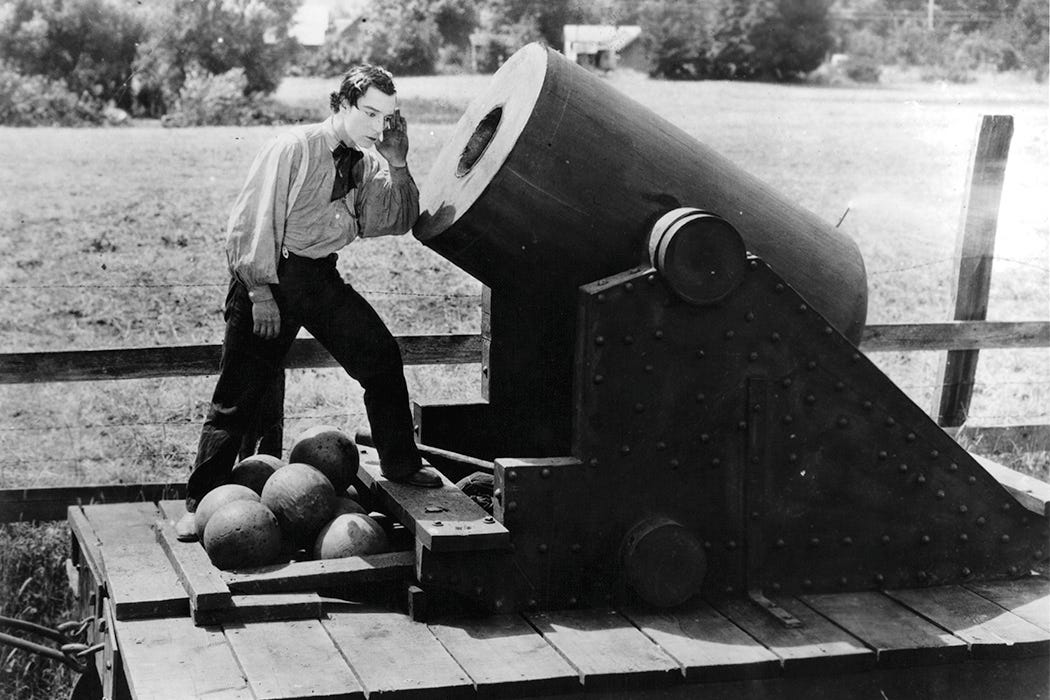

A heads up to readers in the Boston area: Tomorrow night (Wednesday, April 13), I’ll be appearing on the stage of Brookline’s Coolidge Corner Theatre to lead a Q&A with my friend and fellow critic Dana Stevens, author of the excellent, much-praised new book “Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century,” about which I had some nice things to say a few months back. Dana will be signing copies of her book, and a screening of the Keaton classic “The General,” with piano accompaniment by the indefatigable Jeff Rapsis, will start things off at 7 p.m. Please join us!

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.