The Nut Graf1: “Flee,” in theaters and available for VOD rental, is an emotionally overwhelming refugee’s tale told via animation that renders it both universal and unique. (**** stars out of ****)

Why is it that animating a true story can give it more power than simply filming it? “Flee,” one of the best films of 2021 and a likely Oscar candidate for both animation and documentary (the nominations are announced next Tuesday), is the latest in a hybrid genre that has historical precedence but that has heated up in recent years, thanks to films like “Waltz for Bashir” (2008) and “Tower” (2016). The explosion of post-“Maus” graphic-novel memoirs has also fed into the movement, from Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis” (made into a 2007 film) and Alison Bechdel’s “Fun Home” (which became a 2015 Tony Award-winning musical).

“Flee,” in theaters since January and now available as a $6 rental on Amazon, Apple TV, YouTube, and elsewhere, fits comfortably with this company while standing on its own as a heartbreaking, nerve-wracking, ultimately uplifting story of one man’s odyssey to freedom. Amin Nawabi is not his real name and one of the reasons “Flee” is animated is because he didn’t want to be filmed, but the movie’s hero becomes a specific man rather than a symbol as his story unfolds: An Afghan child whose airline pilot father was disappeared by the government, an adolescent refugee marooned for over a year with his family in Moscow, a survivor of human trafficking not once but twice, a solitary teenage émigré in Denmark forced to deny his family’s existence. A gay man born into a culture in which he doesn’t exist.

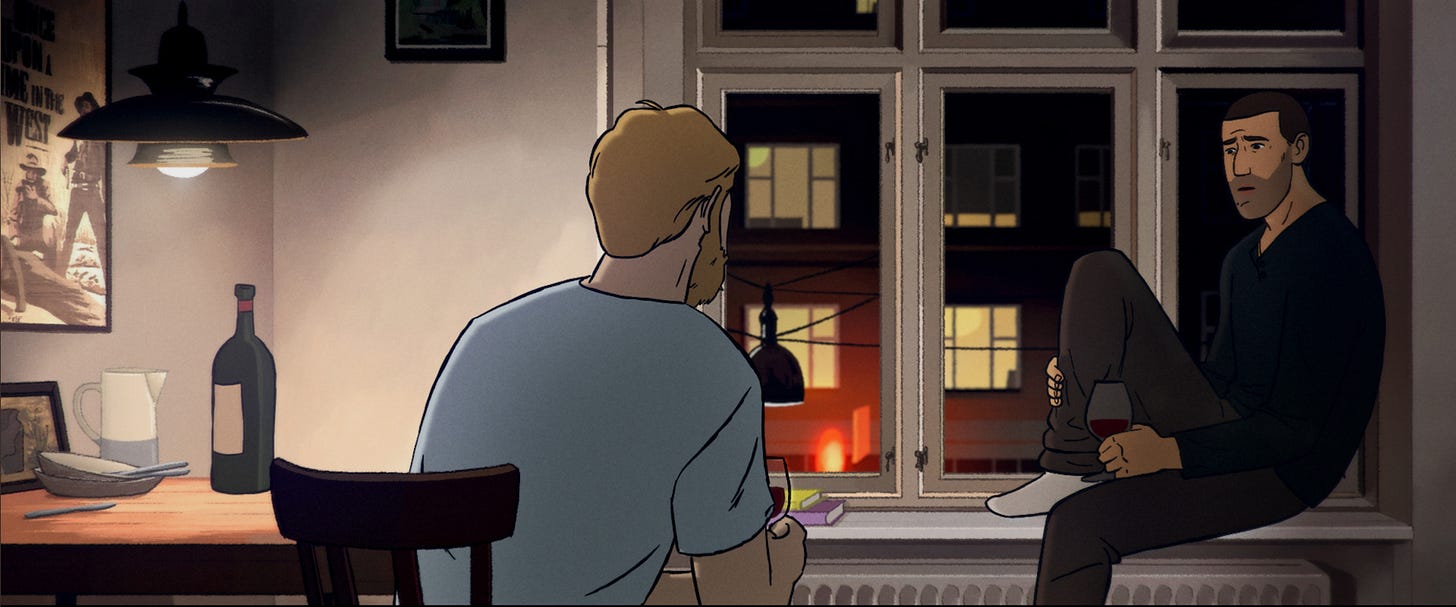

In a blocky yet elegant animation style that turns frighteningly abstract in moments of stress, Amin tells his story to director Jonas Poher Rasmussen, a friend since high school and a gently inquiring presence onscreen. That’s Amin’s voice we hear on the soundtrack, and Rasmussen depicts his subject from above, lying in close-up against a richly patterned rug: It’s a therapy session, and a confessional, too. Mixing animation and sometimes brutal archival news footage, “Flee” traces a journey from late 1980s Kabul, where the last proxy convulsions of the Cold War were playing out (and where the US was backing the mujahideen, helping to create what became the Taliban), to a post-Soviet Moscow of rapacious police thugs, to a Copenhagen of isolation and fear. The transitions from one place to another are the most agonizingly tense moments, including a harrowing nighttime crossing to Estonia and a crossing of the Gulf of Finland in an overcrowded boat. The latter sequence features an encounter with a cruise ship that places the West’s haves, their cameras flashing away on the upper deck, in damning proximity to the world’s have nots.

Rasmussen alternates these scenes with moments of Amin in his present life in Copenhagen, with a loving Danish husband, Kasper, who throughout the film is noodging him to house-hunt and settle down in the country. Amin, meanwhile, is considering relocating to Princeton, NJ, to complete his post-doctoral studies, and the partners’ differing visions of their future creates an anxiety that’s mild in comparison to the horrors of Amin’s past. But that’s partly the point: Amin is uncomfortable going on house tours because he knows “home” is something that can be violently wrenched away. The trauma of having one’s roots yanked up by force reappears as a fear of putting down new ones.

If watching “Flee” feels like a catharsis, making it seems to have been more so. The rest of Amin’s siblings – except for his mother and one brother who remained stuck in Russia for several more years – had found asylum in Sweden, but for two decades Amin chose to live the lie that he was an orphan, for fear that he (or they) might be deported back to Russia or, worse, Afghanistan. In telling his story to Rasmussen, he’s unburdening his soul to a friend but also coming out of a different kind of closet, one built by politics and borders and Western meddling and war.

He had stealth visits to Sweden over the years, though, and “Flee” dramatizes the first reunion as one of the most emotionally powerful moments in the movie. Throughout his life, Amin had hidden his sexuality from his family, keeping his childhood crush on Jean-Claude van Damme a secret (although he imagines the martial arts star mischievously winking at him from a bedroom poster). In Stockholm, there are loving sisters and a much older brother who has become the patriarch in the wake of their father’s death, and there is a moment of held breath as everyone pressures Amin about girlfriends. And then there is a moment that I won’t spoil but that simply gives a viewer hope for the human race and that is worth the price of admission to “Flee” on its own.

Would the movie have worked so well as a filmed documentary rather than an animated one? I don’t think so. The graphic style – the way Amin is cartooned – genericizes him just enough so that his story becomes representative of the modern refugee experience while allowing him to retain his individuality as a person and honoring the specificity of what he endured. (It also makes Amin look a little like a character from the old “Clutch Cargo” TV series, an observation that need only concern other gray-headed sixty-somethings.) “Flee” is a recounting of one man’s life made visible to all of us lucky enough to live on the upper decks. The animation makes it go down easier – the better to jam in our throats.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.