Audrey, the Later Years

For Hepburn's birthday week, a look at her lesser-known films.

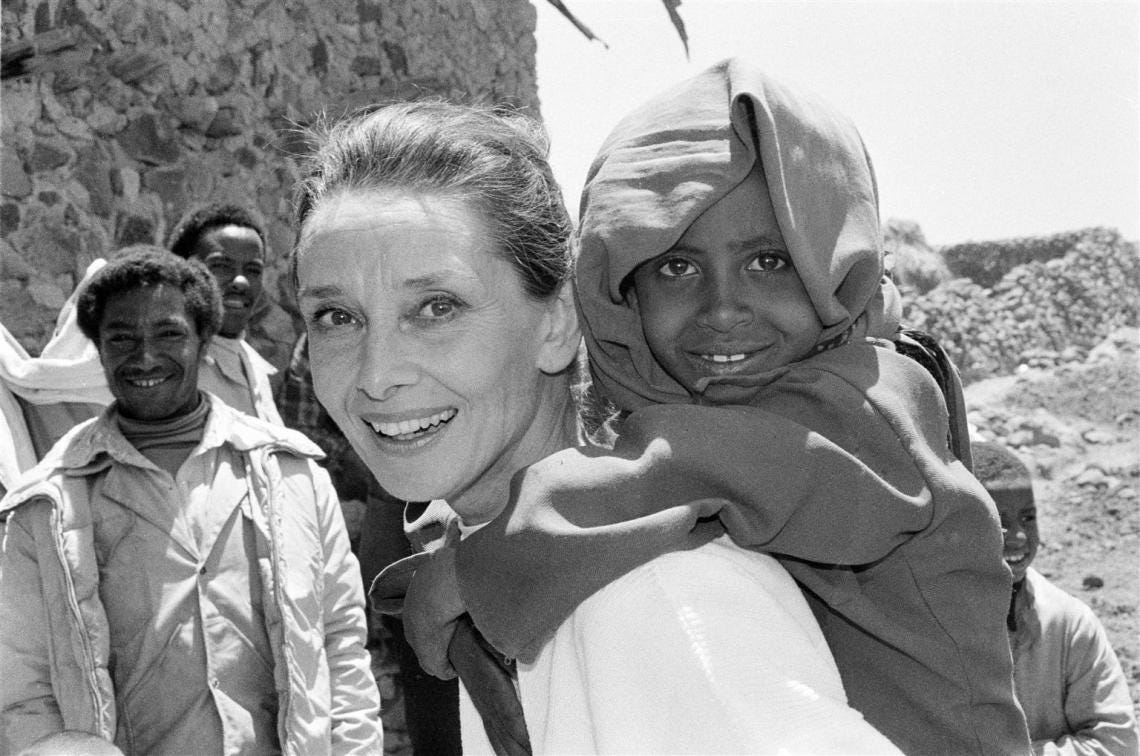

I’m not gonna lie, the news out of Washington, D.C., this morning has me questioning the frivolity of sending out a post about classic movie stars when the SCOTUS is preparing to send us all back to the era in which classic movie stars lived. But the piece was written yesterday and I’ll go ahead and post it as a reminder that grace can exist on earth and to remember a woman whose political activism as UNICEF’s Goodwill Ambassador centered around helping children who were wanted, are here, and are suffering.

Of the movie stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age, only Audrey Hepburn remains alive in popular culture. Bogart, Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, Bette Davis – my students at BU and elsewhere know the names, but only as history. Audrey is still relevant; Audrey still matters, as an idea, as an ideal, as an aspiration, especially to young women, in ways both healthy and not-so. They’ve seen her movies, for one thing, or at least “Roman Holiday” (1953) and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (1961), the first a live-action princess story of the sort spoon-fed to them by Disney since childhood and the second a clash of style and subject matter (she does what for a living? Mickey Rooney’s playing a what?) that must be seen if only to honor its ubiquitous poster. That image – Holly Golightly in her sleeveless black dress with her diamond choker, cigarette holder, and cat – has somehow become a pop signifier of elegance and class that transcends time, fashion, and dodgy racist supporting characters. I’ve seen that image on lunchboxes and backpacks, and it adorns uncounted dorm rooms. When her name comes up in class, eyes light up. She’s still here.

She’s not, of course. Hepburn died in 1993 at 63 of abdominal cancer, too young but also past her greatest moment of impact. She was born on May 4, 1929 – this Wednesday would have been her 92nd birthday – and because she is now timeless in a way very few public figures get to be, it’s difficult to think of her as a normal woman existing and aging in time. Which is to say that Audrey Hepburn made twelve movies after “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” but no one talks about them aside from 1964’s “My Fair Lady,” a universally beloved musical that’s also an elephantine warhorse, one which dubs Hepburn’s singing voice while letting co-star Rex Harrison croak like a grackle. Are the others any good? A couple are actively bad: “The Children’s Hour” (1961) is a pearl-clutching adaptation of the Lillian Hellman play about (shhh) lesbians that was dated before it came out; “Bloodline” (1979), from the Sidney Sheldon novel, is just trash and not even fun trash. But even in her worst movies, Hepburn is still Hepburn, in the movie but somehow apart from it. The “it” that she has – call it star power, charisma, presence, or grace – protects her, and because the camera loves her, so do we.

I’m thinking of her next to last film, “They All Laughed” (1981, above), a flaky Manhattan romantic roundelay from Peter Bogdanovich that has survived its bad karma – co-star Dorothy Stratten was murdered before the film came out – to become a minor cult item. The movie’s supposedly unavailable for streaming (justwatch.com doesn’t even list it) but there’s a decent copy for free viewing on YouTube, and it’s worth a look – a sweet-natured farce about two private detectives (Ben Gazzara and John Ritter) who fall for the errant wives they’re following (Hepburn and Stratten respectively.) Gazzara and Hepburn were in the middle of an affair after having met on “Bloodline” two years earlier, and it seems to give their scenes together an added glow, Hepburn’s inborn elegance warmed even further by real affection.

Of the other post-“Tiffany” films, “My Fair Lady” was bookended by two that are for completists only; they’re not terrible, they’re just product, although fashion hounds will appreciate that they’re the final two films in which Hepburn was dressed by Hubert de Givenchy. “How to Steal a Million” (1966) goes down easiest, a heist caper that’s worth seeing mostly for Hepburn’s pairing with Peter O’Toole, a star as unique as she and one with whom she shares virtually no chemistry – it’s like asking a swan to mate with a giraffe. “Paris When It Sizzles” (1964) is a weird, weird, weird meta-comedy (scripted by George Axelrod, who liked to do that sort of thing) about a playboy screenwriter (William Holden, Hepburn’s “Sabrina” co-star) and a temp typist (Hepburn) who fall in love as they dream up a screenplay that we then see her appear in. With cameos by the likes of Tony Curtis, Marlene Dietrich, Noël Coward, Hepburn’s then-husband Mel Ferrer, and the singing voice of Frank Sinatra, the movie’s rife with in-jokes that haven’t survived its era, but it’s so genuinely odd that you may want to have a gander.

To cut to the chase, the best later Hepburn films are “Charade” (1963), “Two for the Road” (1967), “Wait Until Dark” (1967), and “Robin and Marian” (1976). They couldn’t be more different from each other, yet in each Hepburn does what only a movie star can do: She remains exquisitely herself while serving the movie’s needs. “Charade” is a fun fake-Hitchcock bauble from director Stanley Donen that matches Hepburn with Cary Grant, one of only two pairings she had with much older male stars that made any sense, then and now. (The other was Fred Astaire, in 1957’s “Funny Face”; like Hepburn, both Astaire and Grant seem to exist outside time. Humphrey Bogart in 1954’s “Sabrina” and Gary Cooper in 1957’s “Love in the Afternoon,” not so much.) “Two for The Road,” also from Donen with a smart, acid-etched screenplay by Frederic Raphael, is very much of its time but very much worth your time, if only to enjoy the brittle but real chemistry between Hepburn and Albert Finney as a bickering married couple and to wonder at the perversity of covering half of Hepburn’s face with those huge Oliver Goldsmith sunglasses (below).

“Wait Until Dark” – what, you haven’t seen “Wait Until Dark”? Cue it up right now. An admirably lean suspense thriller about a blind woman trapped in her apartment by three villains seeking a heroin-filled doll, it hasn’t dated a whit and still has the power to jolt even the most jaded audience, i.e., your teenager. It’s also the rare Hepburn vehicle that she holds down on her own, without a romantic co-star, but you do get the bonus of a fabulous young Alan Arkin as the smartest and creepiest of the bad guys.

“Robin and Marian” is Hepburn’s last great movie, and it is heartbreaking precisely because it’s the one item in her filmography that insists on the passing of time. Sean Connery (below) is the aging Robin Hood to Hepburn’s Maid Marian, and the movie’s very much about what happens when a legend becomes a life, a subject that encompasses Sherwood Forest and Hollywood both. This, along with “They All Laughed,” are where Hepburn’s trademark grace becomes all the more precious for its fraying.

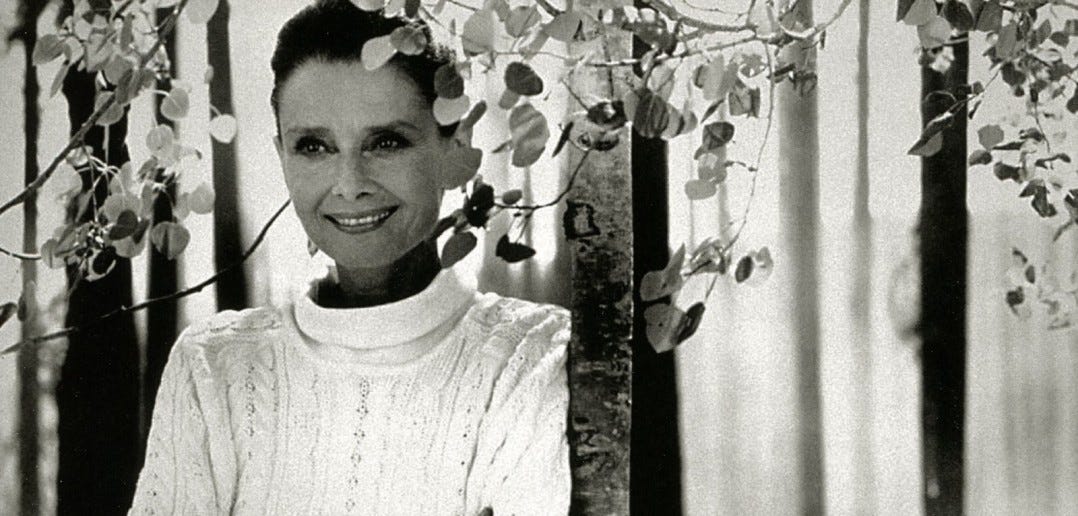

She appeared with Robert Wagner in a 1987 TV movie called “Love Among Thieves” that’s available only on DVD; it was her last starring role. Her final big screen appearance was in Steven Spielberg’s “Always” (1989), a remake of 1943’s “A Guy Named Joe” and one of the more overlooked entries in the director’s filmography. It’s solid if not stellar, but give Spielberg credit for finally casting Hepburn as a being outside of time entirely, a heavenly messenger named Hap who teaches the main character, a recently deceased pilot played by Richard Dreyfuss, to inspire the living and let go of his past. She has only two scenes, but they’re simply beautiful and beautifully simple, the actress radiant in a white cable-knit sweater and as serene as you hope an angel might be. Of course, the script leaves open the possibility that Hap might be more than an angel. Audrey Hepburn as God? There are worse notions with which to entertain ourselves as we whistle along in the dark.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.