Armageddon Outta Here

Some soul-searching over "Armageddon Time," plus brief takes on "Causeway" and season 2 of "The White Lotus."

It’s been a while since I’ve disliked a movie as intensely as “Armageddon Time” (⭐ 1/2, in theaters), and since I appear to be in a fairly vocal minority, with many friends and respected colleagues praising the film, the imposter-syndrome guy who lives inside me (as he/she lives inside us all) has mandated some self-examination. Am I bringing something to the table that keeps me from bonding with writer-director James Gray’s achingly personal – yet, to me, painfully pat – memory film? Or, to quote the Simpsons meme, is it the children who are wrong?

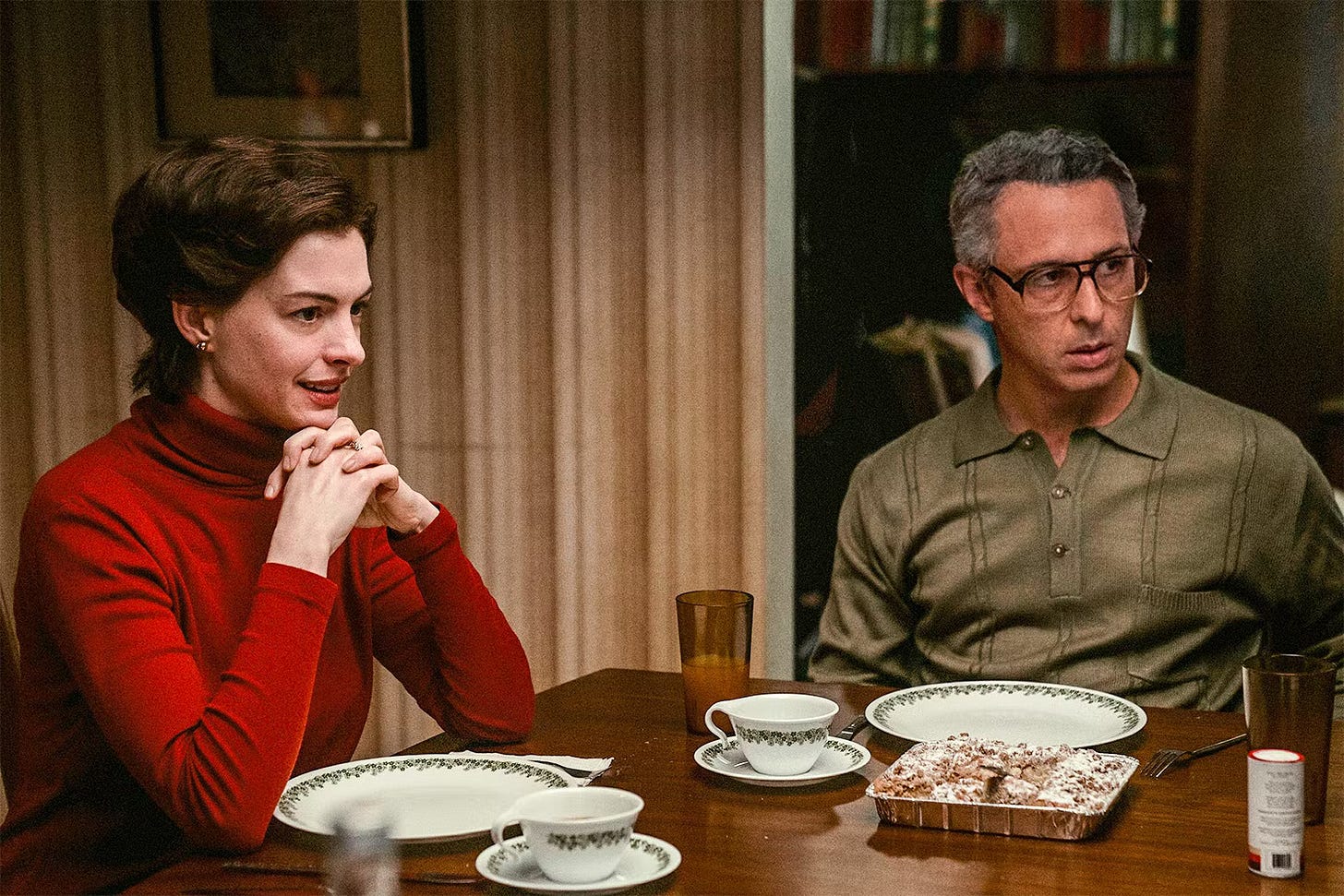

“Armageddon Time” takes place in 1980, as America lurches up to the election that will put Ronald Reagan in the White House. In other words (as the film takes pains to remind us throughout), the beginning of Where We Are Now. At the film’s center is a Queens, NY, sixth grader named Paul Graff (Banks Repeta), sweet-faced but already itching with inarticulate rebellion against… well, everything: A bully of a schoolteacher (Andrew Polk), a thug older brother (Ryan Sell), a mother (Anne Hathaway) who ladles out love spiked with guilt, a father (Jeremy Strong) who alternates bootstrap life advice with leather-belt beatings. The only two people in the kid’s corner – the only two who see him – are Grandpa Aaron (Anthony Hopkins), who fled Eastern Europe as a child, and Johnny Davis (Jaylin Webb), a Black classmate who befriends Paul and who becomes an object lesson in American racism, Jewish complicity, and personal moral failure. Emphasis on “object,” which is where my problems with the movie begin.

My response to “Armageddon Time” is complicated by the fact that James Gray’s resume includes “The Immigrant” (2013), to my mind one of the great films about the American experience and one of the few perfect movies of the new century. “The Immigrant” takes place in 1921 and has one foot in Ellis Island authenticity and one foot in fable, and while it’s largely untroubled by issues of race, it proves that we often see our great-grandparents’ stories more clearly than our own. For his new film, Gray has drawn from his own childhood experiences and in interviews has spoken cogently and passionately about his intentions. He is nothing if not earnest: This is the story of how his younger self became aware of the part his family – and he himself – played in maintaining the cruelties and caste system of American society. How his parents were horrified by the ascension of Reagan yet unthinkingly accepted the trickle-down vision of the world because they stood to benefit from its privileges. And in case you don’t get it, here’s Fred Trump (John Diehl) and his daughter Maryanne (Jessica Chastain) – the Former Guy’s sister – to stridently lecture the students at Paul’s new private school on “earning your way without any” – Chastain spits the word out – “handouts.”

Gray is part of a coterie of talented, even visionary directors currently working – Christopher Nolan and Denis Villeneuve are others – who are almost completely lacking in humor or even a smidgen of the lightness that animates our moments on Earth large and small. These filmmakers belong in the category that Andrew Sarris once labelled “Strained Seriousness,” and their ponderousness is leavened only by their imagination and filmmaking chops (which, to be sure, is often more than enough). In “Armageddon Time,” that seriousness of purpose is yoked to characters who rarely, if ever, escape the green room of stereotype: The clinging, judgmental Jewish mother; the silent, seething patriarch; the wise alter kaker. Stereotypes are rooted in reality, of course, and Gray is building his story from memory, but his writing locks his people into types and the acting compounds the error. Hathaway and Strong are being praised in many quarters for their performances, but what I see in the former is the kind of carefully crafted “underplaying” that caters to the grandstand and in the latter pure, Stanislavskian ham. Hopkins? He’s entertaining but miscast, with an accent that wanders back and forth between Cardiff, Wales, and Ocean Parkway, Brooklyn. The only actor among the adults who convinces – instantly – is Tovah Feldshuh as Grandma Mickey. She has comparatively few scenes, but every moment she’s onscreen you see both the stereotype and the individual – how the former rises out of the latter but never subsumes it.

With Johnny Davis, we don’t get the stereotype or the individual – just an indistinct blur of regret. Jaylin Webb is a perfectly fine young actor, but it would take a performer of unique charisma to make Paul’s friend more than a stand-in for an actual character or a problem to be addressed. The movie’s recreation of “Drop Dead”-era New York City is uncanny in its attention to detail, little of which goes into filling the blanks of this one crucial figure. We get a tiny glimpse of Johnny’s home life, with a grandmother we see once in passing; he has no parents and an unseen brother in Florida who becomes a destination we know will never be reached – the anvil of America’s brutality hangs over Jonny from the start. He likes hip-hop and turns Paul onto the Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight.” And in the most cringingly far-fetched stretch of “Armageddon Time,” we’re asked to believe – spoiler alert – that Johnny would willingly surrender his freedom so that Paul might walk into the future, guilty of conscience but untouched. Because that’s what Black characters do in movies where they’re the only Black characters in sight: Sacrifice themselves for the moral betterment of the White hero. It worked when Sidney Poitier jumped off the train to save Tony Curtis’ life in “The Defiant Ones” (1958), and Gray is hoping, with all the best intentions and underwritten characterizations, that it will work now.

And apparently it does. (A number of Black film critics, including Odie Henderson, my replacement at the Boston Globe, would beg to differ.) My own uncertainty regarding “Armageddon Time” – the reason I question and probe my dislike of the movie – may be rooted in my personal position as a close observer of, but not a participant in, its cultural milieu. I’m a Boston WASP married to a Jewish woman who was raised in western Long Island hard by the Five Towns; her parents grew up in Brooklyn and her maternal grandparents were named Irving and Esther, the same names as Strong’s and Hathaway’s characters in the movie. Both our children have been bat mitzvahed; I haven’t been in a church in decades, but I’ve participated in more seders than I can count. My mother-in-law says I know more Yiddish than she does and maybe that’s true – but all of that still leaves me outside the window of my wife’s parents’ culture, their America, looking in. So are those actually stereotypes I’m seeing or am I unable to fill the outlines Gray draws with remembered or imagined life? Is the movie at fault, or am I? All I know is that I came home from the screening and told my wife that the parents in the movie had the same names as her Bubbe and Grampa. “They were cliches,” I said. “But my grandparents weren’t cliches,” she said. “I know they weren’t,” I agreed. “But this movie turned them into one.”

There are some problems with “Causeway” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐), a new drama simultaneously arriving in theaters and on Apple TV+, but a thinly imagined Black character isn’t one of them. Directed by Lila Neugebauer – a TV director making her first feature – it’s a quiet, empathetic drama about an Afghanistan War veteran named Lynsey (Jennifer Lawrence, hushed and excellent), recovering from a brain injury sustained in an IED explosion, and her deepening friendship with James (Brian Tyree Henry), the owner of an auto shop in the hardscrabble New Orleans neighborhood in which they both live. Missing a leg from a car accident whose details slowly seep in over the course of the movie, James is a wounded outsider too, but Henry plays him with a minimum of self-pity, and what’s there makes sense. The actor is one of the weary godsends of the modern screen, whether as the rapper Paper Boi in “Atlanta,” the Thomas the Tank Engine-obsessed assassin in “Bullet Train,” or holding down the center of indie comedy-drama “The Outside Story,” and he knows how to fill a role so you sense the particulars of where a character has been and where he is now. “Causeway” is disarmingly gentle toward its two battered souls, and a little too cautious about how they connect – is this a romance? does it want to be? – and it rolls to a quizzical halt rather than ending. The filmmakers are so careful about dodging the snares and assumptions of a template for interracial drama that goes back to “A Patch of Blue” (1965, and Sidney Poitier again, because who else?) that they risk rendering their movie inert. Still, their approach to the two people at the center of the tale is honest and honorable, and the actors respond in gracious kind.

I’ve watched the first four episodes of “The White Lotus” season two (⭐ ⭐ ⭐) – HBO has made the initial five available for review – and I’ll say for now that fans of the first iteration of Mike White’s “Lifestyles of the Rich and Awful” should recalibrate their expectations a bit. We’re in Sicily, at a deluxe beachside “White Lotus” resort in view of Mt. Etna, whose distant smoldering serves multiple metaphors. The ruthless power dynamics that in season one were rooted in money and class and (to a lesser extent) race have been replaced by those governed by sex – by the social and financial transactions prompted by lust and by the deceptions, self- and otherwise, that allow the characters to function until they’ve lied themselves into a corner. There’s some slamming-door farce involved, with players that include a Hollywood producer with a sex addiction (Michael Imperioli), his embarrassing old goat of a father (F. Murray Abraham); and a college-age son (Adam DiMarco) trying to balance scoring with being sensitively woke; a preening finance bro (Theo James) and his Instagram-ready wife (Meghann Fahy); a newly hatched Internet millionaire (Will Sharpe) and his wife (Aubrey Plaza, as gloriously dour as always and a welcome black cloud to every sunny scene); returning character Tanya McQuoid (Jennifer Coolidge) sozzled in self-pity and making her put-upon assistant (Haley Lu Richardson) dance like a monkey on a string; the resort’s tightly wound manager (Sabrina Impacciatore); and Lucia (the aptly named Simona Tabasco) and Mia (Beatrice Grannò), two local escorts hoping to shake loose some cash while having a good time.

The upstairs/downstairs calculus of rich guests and surly servants is minimized here for White’s finely satiric eye on the ways people simply want what (and who) they can’t have and don’t want who they can, with money only adding a tanning-oil layer of corruption atop the yearning. This may be a harder sell than the open mockery of the first “White Lotus,” but, four episodes in, it’s paying dividends. More to come as the season progresses.

Thoughts? Comments? Don’t hesitate to share.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how: