A Handmaid's Tale (Leon Vitali 1948-2022)

On the mystery and necessity of shadow collaborators.

Leon Vitali died last week, and if you’re saying, “Who?,” that’s pretty much the point. In a film industry and a popular culture that lionizes the individual, Vitali represented the many unknown names and faces without whom the individual would have no glory. He was a factotum – the person who gets things done and receives no thanks for it.

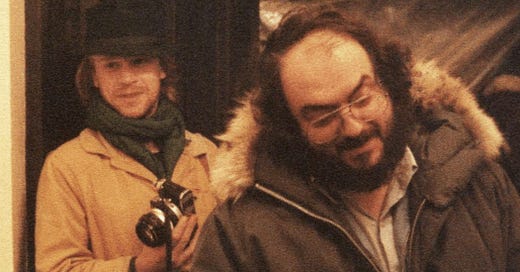

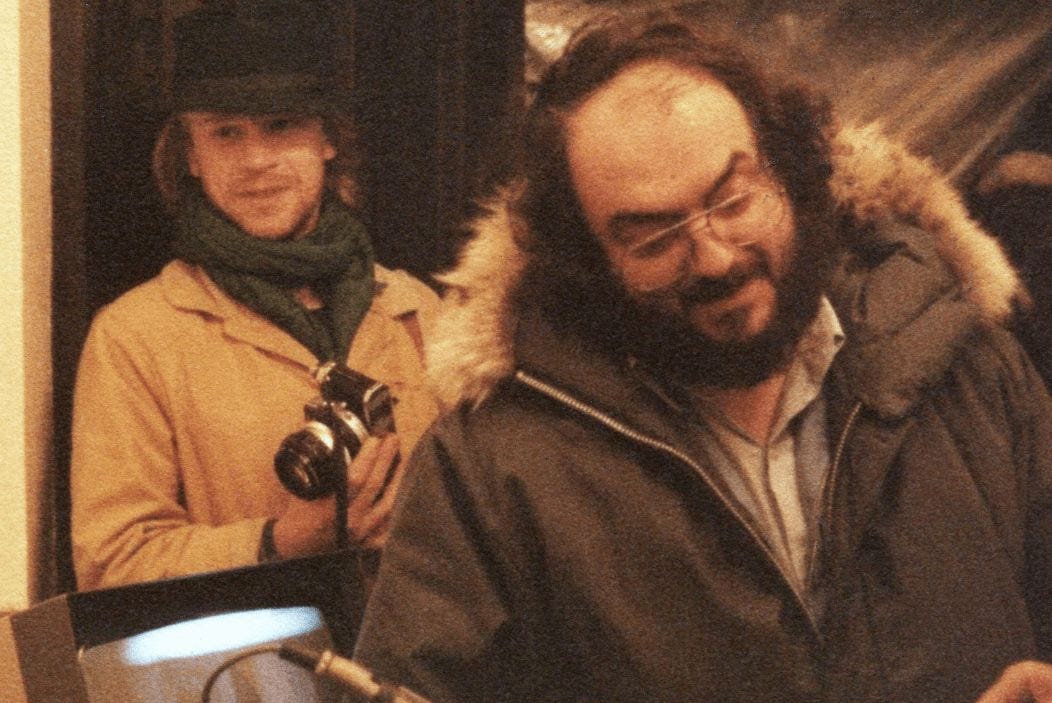

Specifically, he was Stanley Kubrick’s personal assistant from the late 1970s until well after the legendary director’s death in 1999. Vitali, born in 1948, was a successful young actor of London stage and screen when he was cast as the tragic Lord Bullingdon opposite Ryan O’Neal in Kubrick’s 1975 film “Barry Lyndon.” During the production, he was so taken with the business of filmmaking and the mastery of this particular filmmaker that he quit acting and signed himself over for a lifetime’s indentured service. His only notable role after that was as the man in the red cloak during the orgy sequence in “Eyes Wide Shut.”

It was Vitali who went to America to audition 5,000 little boys for “The Shining” and returned with Danny Lloyd, and it was Vitali who, sent to find a creepy young girl for the film’s hallway sequence, came back with twins, inspired by a famous Diane Arbus photograph.

It was Vitali who convinced Kubrick that R. Lee Ermey, the military advisor on “Full Metal Jacket,” had the charisma of a great on-screen actor. And it was Vitali who helped shepherd “Eyes Wide Shut” to theaters after the director unexpectedly died upon completion of editing.

Both Lloyd and Ermey have credited Leon with coaching their performances, raising the notion that this invisible man was at times a shadow director. That Vitali is known at all – that his passing warranted obituaries in major newspapers – is thanks to “Filmworker,” the fond and mildly unsettling 2018 documentary made about him by Tony Zierra. It’s available on Amazon and elsewhere for a $3 rental and is worth seeking out. The title comes from Vitali’s occupation as listed on his passport, and it’s instructive to think about that wording. Leon didn’t see himself as a “filmmaker” but a “film worker,” a laborer striving for the benefit of something – or someone – greater than himself. As I wrote in my Boston Globe review (available in full behind the paper’s paywall), Zierra’s documentary

is, among other things, a reminder of the egolessness necessary for great egos to flourish … Vitali is presented as having been critical to the day-to-day functioning of Kubrick Inc., dispatched to deal with everything from casting to archival work to the color timing of prints to building a compound for the Kubrick family cats.

It wasn’t always easy. The Great Man had a temper that is described in the film as “vitriolic” and that could explode at any moment; one Christmas, he spent a half hour yelling at Leon and then gave him presents. We see to-do lists that say simply, “LEON — BILLIARD ROOM.” “Filmworker” brings on Vitali’s brothers and sisters to talk about growing up with a physically and verbally abusive father, prompting a viewer to ponder the many ways a man can feel at home.

We also hear from Leon’s three grown children, who say things like, “If it was a bad day for Stanley, it was a bad day for Leon and a bad day for me.” Why did they and he put up with it at all? Why did Vitali walk away from acting and devote himself to the thankless role of artistic handmaiden?

The question hovers over the documentary as it does over Leon Vitali’s long, subordinate life. (Asked by Zierra in 2018 if he’s still working for Stanley, Leon looks at him as if he’s crazy and replies, “Of course.”) Watching “Filmworker” prompts a viewer to contemplate the tens of thousands of men and women who make possible the art we love and whom we’ve never heard of — and mostly never will.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.