What To Watch: "Once Within A Time"

Plus: "Anatomy of a Fall," "The Burial," and Wes Anderson's Netflix shorts.

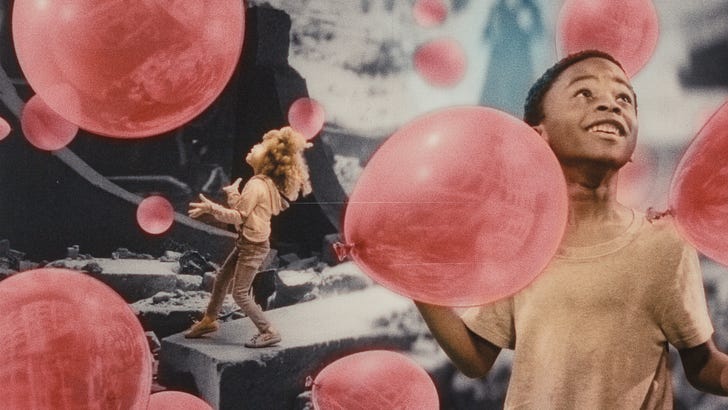

The strangest movie opening today is also the most eerily beautiful: “Once Within A Time” (in theaters, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2) is a cinematic parable, just under an hour long, from our wayward Jeremiah of the movies, Godfrey Reggio. Reggio, you may recall, is the Christian Brotherhood monk who took time out from working with youth gangs and the ACLU to make “Koyaanisqatsi” (1982), a wordless documentary/allegory about the collapse of nature in the face of man’s depredations that became a sizable and influential independent hit. (The Philip Glass score helped, as did Francis Ford Coppola coming on board as presenter.) Reggio made it a trilogy with “Powaqqatsi” (1988) and “Naqoyqatsi” (2002), the last taking advantage of digital filmmaking techniques to mount a broadside against technology – a case of using the devil’s tools against him. “Visitors” (2013) was a dreamlike study of human faces as they watch the screens that have subsumed most of our waking hours, and now we have “Once Within a Time,” Reggio’s first fictional narrative. It starts a city-by-city roadshow release this weekend, first in New York, then in other cities before arriving in Boston on November 3rd.

The title is a kind of prism: “Once Within A Time” is a story of our cultural moment that seems to unfold outside of time itself, entwining a Garden of Eden metaphor with a seduction-of-the-innocents cry of warning. Visually and thematically, “Once Within A Time” evokes Lewis Carroll, 19th century photography, German Expressionist cinema, the films of George Melies, and avant-garde film of the late silent and early sound eras; its techniques encompass puppetry, stop-motion animation, film tinting, shadow-play, and an approach to costume and set design that suggests Max Reinhardt on a mushroom binge. All of this is given a mysterious digital wash that places it in both the future and the past – it’s as though D.W. Griffith and Fritz Lang took a time machine to the 21st century, looked around in horror, then hightailed it back to 1927 to make “Metropolis,” with Griffith writing the script.

Throughout his career, Reggio has posited technology as the sickness that homo sapiens has brought to bear upon the planet, and he hasn’t changed his tune here other than to update the gadgets he’s railing against. But while the film’s swipes against our phone-obsessed modernity are accurate, they’re also obvious; “Once Within A Time” works best when it’s operating on the level of a fairy tale from our cultural subconscious. Its message is carried in the DNA of its rapturous steampunk images, the angelic faces of the child actors, and the nightmarishness of the jack-in-the-box baddies plaguing the filmmakers’ garden, John Flax especially unnerving as a kind of combination Big Brother/Pinky Lee luring the kids to their audio-visual doom. Did I mention Mike Tyson is in this too? The boxer plays “the Mentor,” dressed in Afro-retro-futurist robes and talking in a saxophone squawk as he rallies the children to do … what I’m not exactly sure. But it’s something to see. (And to hear, with Glass contributing yet another ear-bending new score, this one with calliope rhythms augmented by Iranian singer Sussan Deyhim, above, who appears in the film as a giant tree.)

Reggio’s co-director on “Once Within A Time” is Jon Kane, who has worked with him since “Naqoyqatsi” and who functions, essentially, as Godfrey’s réalisateur, translating his ideas into something that can be built, staged, performed, and filmed. In the half-hour making-of documentary available online – itself as entertaining, if more linear, than the feature – you can see the process at work, Reggio a ringer for Rasputin the mad monk as he spouts impossible visions from the corner of a conference room and Kane looking around at his stalwart crew with an air of “how’re we gonna pull this off?” But they do. And they did. “Once Within A Time” is the product of a ferociously creative hive mind, at whose apex sits an Old Testament prophet furiously warning us of the apocalypse at hand.

(As a mark of the serendipity of the universe, allow me to confess my own part in their creative partnership. Back in 2000, I interviewed Reggio for the New York Times Sunday Arts and Leisure section; the occasion was a screening of “Koyaanisqatsi” with a live performance of the Glass score, but the interview, which took place at the composer’s house in the East Village, was mostly about the difficulty Godfrey was having raising money for “Naqoyqatsi,” the final film in the “Qatsi” trilogy. Two things came out of that article. First, the director Steven Soderbergh read it and immediately called Reggio with an open checkbook, funding “Naqoyqatsi” across the finish line to completion; Soderbergh serves as presenter on the new film. Second, as I was hanging out in a Brooklyn playground with my then-toddlers, I mentioned to a neighboring dad, a commercial filmmaker and DJ who’d become a friend in the trenches of new parenthood, that I was writing a piece about Godfrey Reggio. My friend was a fan and asked if I wouldn’t mind putting the two of them together. This I did, my friend ended up editing “Naqoyqatsi,” and, 23 years later, Jon Kane is the man tasked with taking the Hieronymus Bosch paintings in Godfrey’s head and turning them into something the rest of the world can see. I admit to being pleased by this particular example of the Butterfly Effect, perhaps the only actual contribution to cinema I have made in 45 years as a critic.)

Also in theaters this week: The powerhouse “Anatomy of a Fall” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐), which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes last May and which is a showcase for Sandra Hüller (above) as a best-selling writer of thrillers whose husband dies falling out a window. Or was he pushed? You get a classic courtroom melodrama, yes, but in writer-director Justine Triet’s hand you also get a full-blooded dissection of the pressures brought to bear on a successful woman and her marriage, as well as a working example of our need for real-life villains. It’s a tricky film and you’ll probably argue with the ending – which is the intent, I have to believe – but if for no other reason attend “Anatomy of a Fall” for Hüller’s galvanic performance, with its emotions writ large and, when you least expect it, profoundly subtle.

Also opening in theaters this week: “Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour,” which has already broken box office records before anyone has seen it and which merely confirms that the singer is queen of Planet Earth and we are but her subjects. Resistance is futile.

Given that the multiplexes will be filled with screaming Swifties this weekend, you may want to stay home. I can recommend – just – “The Burial” (streaming on Amazon Prime, ⭐ ⭐ 1/2), a courtroom drama that’s much less incisive than “Anatomy of a Fall” but that functions as serviceable VOD comfort food on the strength of its two lead performances. That would be Tommy Lee Jones (above left) as a sly grandpa of a Mississippi mortician who sues the Canadian funeral-home conglomerate that bilked him and Jamie Foxx (above right) as his hambone of an attorney, grown fat on personal injury lawsuits but biting into this contract dispute with extra relish. (The movie is loosely based on an actual case from the late 1990s.) It’s an easy watch, with solid supporting performances from Jurnee Smollett as Foxx’s opposing attorney and Mamoudou Athie (“Uncorked”) as a young lawyer who may be the sharpest person in the room, and a rather more tartly aware take on race than is usual for these movies. But the photography and editing are at times surprisingly clumsy (did they even shoot enough coverage for the editor to work with?) and any lawyer worth his or her degree may have trouble with the way certain aspects of the case are resolved. For director Maggie Betts it’s a half step down from her previous film, the striking convent drama “Novitiate.” Maybe she can appeal.

I’m belatedly catching up with the four Wes Anderson shorts that went up on Netflix recently, all adaptations of Roald Dahl short stories and all quite enjoyable, if of varying quality. It’s not often remembered that Dahl wrote short stories for adults – eerie little tales that owe quite a bit to Saki – and I remain haunted by one I read in early adolescence: “Royal Jelly,” about a baby that by story’s end is turning into a giant bee. That’s not one of the tales adapted by Anderson (although maybe it should have been); instead, our auteur applies his OCD filmmaking style to the more whimsically ironic of Dahl’s stories, with a rotating cast and flyaway sets. The longest of the four is “The Wonderful World of Henry Sugar” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐), which dovetails neatly with Anderson’s love of nested narratives: Here, Dahl (Ralph Fiennes) regales us from his study with the story of a jaded dilettante (Benedict Cumberbatch) whose life is changed by the discovery of a case history by a doctor (Dev Patel) about a man (Ben Kingsley) with a peculiar talent. The actors dryly narrate the action as they’re enacting it, and so Anderson seems to have perfected the art of simultaneously showing and telling – a tinkertoy approach to cinema that can pall over the length of a feature but plays with delightful brio in a short.

The other three films are around 18 minutes each – more like 14 minutes once you discount the Netflix end titles for every language. “Poison” (⭐ ⭐ 1/2) is the weakest of the bunch, with Patel, Cumberbatch, and Kingsley in a Kipling-esque slog about a man trapped in bed with a poisonous snake. “The Swan” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2) is a disturbing story of childhood cruelty that reads like “James and the Giant Peach” with the gloves off – compelling, but it lands with a crash. “The Ratcatcher” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐) is a keeper, though – a three-hander about a garage mechanic (Rupert Friend) with a rat problem, Richard Ayoade as his neighbor/narrator, and Fiennes again, fantastically creepy as a pest removal expert who may be too close to his quarry. (“You gots to know rats if you wants to catch ‘em,” he says insinuatingly.) It’s not much more than a skit, but it gets under your skin and stays there.

If this past week has been as soul-wrecking for you as it has been for me and millions of others, I do hope you’re practicing self-care to the extent that you can. Aside from re-posting a few especially well-expressed statements of grief from other people, I’ve been resisting commenting on social media, as I feel that it pushes raw emotions closer to performance and, sadly, seems to only fuel further rancor and divisiveness. I wish more people would do the same, and I wish they’d get their news from reputable news-gathering sources rather than Facebook. If you’re seeking a brief respite of solace, I can recommend the just-released Joni Mitchell Archives, vol. 3: The Asylum Years (1972 – 1975), six hours of demos, concert recordings, and alternate takes from the years of “For The Roses,” “Court and Spark,” and “The Hissing of Summer Lawns.” It’s a balm but it’s unfortunately not available on Spotify, as Joni has joined with Neil Young to protest the service’s artist-royalty structure. You can find the whole set on Tidal, though, and also on YouTube. I’ve found sustenance as well in a cut off the new Sufjan Stevens album “Javelin” — the inaptly named “Shit Talk,” a rueful break-up song that overlaps into political dimensions and whose chorus of “I don’t want to fight at all” is echoing this week in my exhausted heart. Stay well, all.

Comments? Please don’t hesitate to weigh in.

If this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List spoke to you, feel free to pass it along to others.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be eternally grateful — here’s how.

You can give a paid Watch List gift subscription to your movie-mad friends —

Or refer friends to the Watch List and get credit for new subscribers. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll:

Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

Get a 6 month comp for 25 referrals. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

There’s a leaderboard where you can track your shares. To learn more, check out Substack’s FAQ.