What to Watch: "May December"

Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore give brilliantly tricky performances as an actress and her scandalous subject in Todd Haynes' new drama.

The unsettling hall of mirrors that is “May December” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2, in theaters now, on Netflix December 1) forces a moviegoer to reflect on notions of identity, performance, intent, morality, ego, abuse – all good, pulpy stuff. What doesn’t enter into the picture is love, despite the implied word “romance” in the film’s title, and despite the happy domestic façade that Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Julianne Moore) presents to a world that hates her. Directed by Todd Haynes with an astonishingly nimble mixture of tones – comedy, drama, psychological horror show, camp – it’s a movie about acting in which the performances themselves are multi-layered and symbiotic, clashing and merging into one. It’s a little as if Bergman’s “Persona” had been remade by the Real Housewives of Savannah.

A suburban neighborhood outside that city is where Elizabeth Berry (Natalie Portman) arrives at the film’s start on a mission to transform herself into someone else. Elizabeth is a famous Hollywood actress – as A-list as, say, Natalie Portman – who has been cast to play Gracie in an upcoming film. Or, rather, the Gracie of 22 years earlier, when the older woman made national headlines as a married mother of three who fell in love with a 14-year-old boy, had his child, and served prison time.

“May December” takes the basics of the Mary Kay Letourneau story for its bones and builds atop it a power play between two women, each of whom wants to control the idea of Gracie in the public eye. The surface is all Georgia peaches and cream and air kisses, but underneath the film’s deceptively gauzy style, the knives are out.

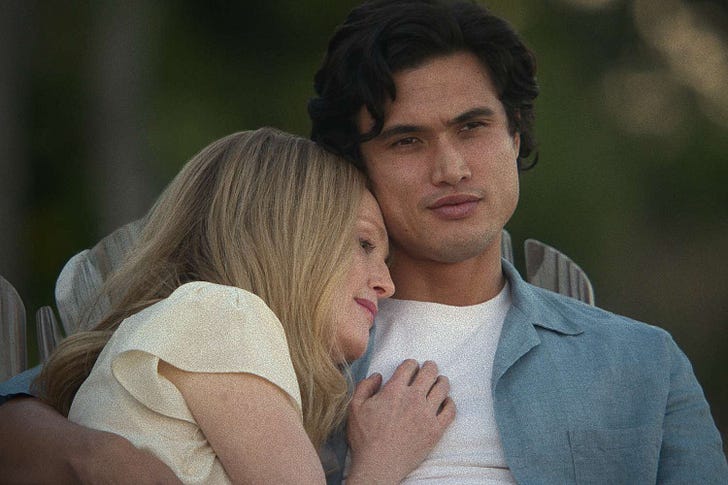

Gracie is still married to the much younger Joe (Charles Melton, above), who now works as a radiology technician; their older daughter (Piper Curda) is off at college, and their twins, Charlie (Gabriel Ching) and Mary (Elizabeth Yu), are about to graduate from high school. Milling in the background of town are Gracie’s grown children from a first marriage, including an angry, sarcastic son, Georgie (Cory Michael Smith). The arrival of a movie star throws everybody off balance, enough for rawer and more honest feelings to shine through the cracks of the family’s smiles.

Years after the scandal, Gracie yearns for normality, but she may also miss the fame, and she still doesn’t think she got a fair shake from America’s tabloid readers. To the contrary: Anonymous boxes of dog shit still arrive in the mail, and while Gracie’s baking business seems to be a success, it’s being propped up by a diminishing group of friends. The act has started to lose its luster. Maybe a Hollywood movie will polish it anew. Melodramatic music wells up on the soundtrack like pus from a wound; could it be ironic punctuation, or Gracie’s inner score, or is Haynes is mocking the soap operas we make for ourselves? (It’s actually a repurposing of Michel Legrand’s music from the 1971 Joseph Losey film “The Go-Between.”)

On one level, “May December” is about how abuse percolates through a family for years, weakening the foundations of every relationship. Melton’s performance very gradually breaks a viewer’s heart: The seemingly content and confident Joe is still a damaged child, younger even than his own children – a rooftop scene where he gets high for the first time with his teenage son shifts from comedy to bone-deep sadness in a matter of seconds. Georgie’s bitterness toward the mother who abandoned him burns through the movie like a fuse headed for a payload. Elizabeth the movie star takes this all in and files it away. “I like to look for the seeds,” she tells the woman she thinks of as mulch.

Which isn’t as easy as it looks. If Portman’s character appears to be a simple sort of parasite, one who makes her living by absorbing the lives of others, Moore’s Gracie is an unknowable mixture of trauma, steely control, delusion, and Southern charm. The movie’s essentially a passive-aggressive pas de deux, and the scenes in which the actress studies her subject behind the guise of entre-nous friendship, sizing her up like a mark and jotting down notes as soon as Gracie leaves the room, are brutally, comically honest about the creative work – the “process” – involved in becoming a different person. (Watching Portman, I thought of an anecdote the former Boston Globe reporter Sacha Pfeiffer told me about being shadowed by Rachel McAdams during pre-production for 2015’s “Spotlight,” in which McAdams played Pfeiffer. The two were walking down a hallway together and at one point the actress dropped back behind the journalist, who realized with a start that McAdams was discreetly studying her gait.)

As “May December” progresses, the gamesmanship becomes a struggle between two women for control of what Gracie Atherton-Yoo means. Not the woman herself, but the story she tells in and to the culture. The actress wants to control the meaning because she has no core personality of her own, which may be a hazard of the profession but is also who she is(n’t). Grace needs to control the meaning, because otherwise she’d have to confront the fact that she’s the victimizer instead of the victim. One woman wants to build something, the other is terrified that what she built will be exposed and destroyed. All this with smiles, feints, genteel manipulations, and a sequence in a mirrored bathroom where Haynes consciously evokes “Persona” in ways that can make your hair stand on end. It’s a movie by turns hilarious and terrifying, and it pirouettes into a twist that takes everything you think about these two predators and stands it on its head.

If you asked me to name the greatest filmmakers currently working, I’d probably come up with a fairly long laundry list, and on it would be a lot of expected names: Scorsese, Lynch, Denis, Almodovar, Bong, Park, del Toro. Et cetera. It’s a good prompt for starting a bar argument, especially if the bar is next door to an arthouse cinema. Ask me who my favorite working directors are, though, and you might get an entirely different list, and toward the top of it many days would probably be Todd Haynes. I’d say the man hasn’t made a bad movie in 35 years, but that would be to ignore “Velvet Goldmine” (1998), a fictionalized David Bowie saga hamstrung by the lack of any David Bowie music, and, to a lesser extent, “Dark Waters” (2019), a corporate whistleblower drama that is competent and relatively faceless. Against that, there’s “Far From Heaven” (2002), which updates Douglas Sirk’s 1955 melodrama “All That Heaven Allows” to address race and sexuality as well as class; “Carol” (2015), a swooning lesbian love story; the psycho-environmental horror drama “Safe” (1995), which marked Haynes’ first of five collaborations with Julianne Moore; and the brilliant “I’m Not There” (2007), which takes the only sensible approach to a Bob Dylan bio-pic, which is to cast seven different actors as the many sides of Bob. Then there’s the audacious “Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story,” a legendary underground film from 1987 that uses a cast of Barbie dolls to dramatize the singer’s struggle with anorexia nervosa; it’s ironic, deeply sympathetic, and available only via bootleg thanks to a copyright lawsuit filed by Richard Carpenter.

What I love about Haynes is the way he couples an obsessive reverence for the cinema of the past with a modern dramatic sensibility and a fluid filmmaking style in which form is endlessly mutable in the service of function. That, and his empathy for outsiders in all their lost, dangerous subversiveness: Bob Dylan, Karen Carpenter (yes, really), Carol, the deaf children of “Wonderstruck” (2013), the Velvet Underground in his 2020 documentary of the same name. A queer auteur who has brought a fringe outlook to the commercial mainstream, Haynes is both one of the gentlest and most gonzo of American independent filmmakers, and more than a lot of his peers, he’s drawn to characters who battle their way through this world as individuals, despite society’s crippling insistence that they conform. Sometimes those characters win, sometimes they lose. Sometimes, like Gracie Atherton-Yoo, the line between winning and losing disappears in a thicket of self-loathing and self-love. “May December” is a war of wills between a woman who sheds skins as a matter of art and a woman who invents selves as an act of survival, and it leaves a viewer happily concussed.

Unrelated birding link of the week, originally published in March: Josh Nathan-Kasiz’s impressively researched and elegantly written history of Flaco, the Eurasian eagle-owl that escaped New York’s Central Park Zoo after a lifetime of captivity and has now survived for nearly a year on a diet of park rats and other unlucky vertebrates, with a recent foray down to the East Village because maybe he wanted to hear a band. Nathan-Kasiz wanders from ancient Rome to COVID-era America as he ponders the meaning of a giant feathered predator making a new life in an urban wilderness. Which, honestly, sounds like most New Yorkers.

Comments? Other recommendations? Please don’t hesitate to weigh in.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, feel free to pass it along to others.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be eternally grateful — here’s how.

You can give a paid Watch List gift subscription to your movie-mad friends —

Or refer friends to the Watch List and get credit for new subscribers. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll:

Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

Get a 6 month comp for 25 referrals. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

There’s a leaderboard where you can track your shares. To learn more, check out Substack’s FAQ.