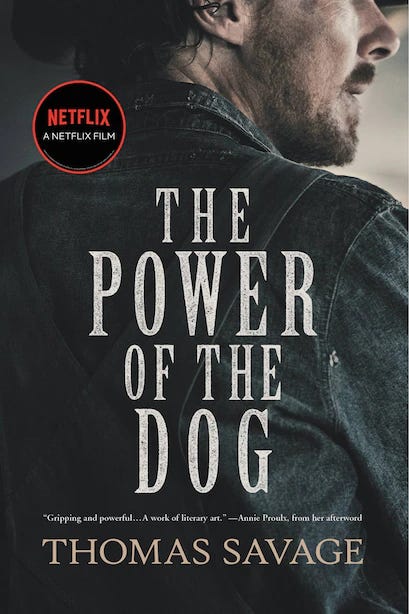

I’ll be writing something about Jane Campion’s excellent new film, “The Power of the Dog,” when it debuts on Netflix on Wednesday, but for the moment I want to pose a question: What does a movie owe to the book on which it was based? I ask because Netflix sent critics a copy of the 1967 source novel by the late Thomas Savage, and I could have read it before setting out to write about the film but chose not to. I did flip the book open to the first page and read the opening paragraph, and that was all I needed to know that A) the novel is written in a very distinctive voice and B) it’s not the same voice as the movie. And the movie is what a movie critic should be attending to. I want to watch Campion’s “The Power of the Dog” without hearing the ghost of Savage’s, so why is Netflix even sending me the book?

Still, I go back and forth about this. Reading the book ahead of time automatically means I’ll compare it to the movie, since I can’t unread it and it will always be lurking in my head. Is that fair to readers who haven’t read the book, as is most likely the case? The answer is it depends. I stopped reading the “Harry Potter” novels after the first one (my kids kept plowing on) because everyone was flipping out over which house-elf or random Muggle got left out of the film adaptations, and my job was to weigh the movies as movies. On the other hand, if I hadn’t read Alice Sebold’s “The Lovely Bones” ahead of time, I wouldn’t have been able to specify the ways in which the 2009 Peter Jackson film version goes mind-bendingly wrong. (It’s not easy to get a terrible performance out of Stanley Tucci.) If I hadn’t read Jonathan Safran Foer’s “Everything Is Illuminated,” I’d never have known that Liev Schreiber’s 2005 movie changes the ethnicity of one key character and thereby alters the story’s entire meaning (all of us are complicit) to something quite a bit safer (all of us are victims).

Moviegoers have it easier. You’ve either read the book or you haven’t, and you aren’t bothered by notions of duty. (Presumably.) And of course it varies according to the situation. A blockbuster like “Dune” is pre-sold on the original novel’s pop culture status, and the assumption going in is that audiences will want to see Arrakis brought faithfully to the screen, sandworms and all. Filmmakers who fiddle with that do so at their peril: Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Brian De Palma’s “The Bonfire of the Vanities.” On the other hand, adaptations of a classic like “Little Women” can be bent to the tenor of their times, as all four film versions have been (not just Greta Gerwig’s). Movies that deliver the exact same emotional experience as the book are rare — “To Kill a Mockingbird” is probably the gold standard in that regard — and maybe they should be. In the end, the key variable may be the filmmaker. Jane Campion is a director who likes to take risks, and it’s her vision I’m interested in seeing. I can always read the original later, and I probably will.

How about you: What books do you think have been especially well-adapted or maladapted to the screen? Are there movies that are better than the book? Is the experience of an adaptation enriched if you have the original in mind? To restate the question at the top: What, if anything, does a movie owe to its literary source?

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.