The Monroe Doctrine

"Blonde," the Netflix Marilyn Monroe movie, punishes Norma Jeane for our sins.

Which Marilyn do you prefer? The smiling temptress, skirt billowing up in the subway breeze? The doe-eyed innocent, unaware of all the cartoon klaxon horns she sets off in 1950s men? Maybe the serious actress, unfairly mocked for her Stanislavskian pretensions, or the sex symbol terrified to act in front of a camera. The silk-screened icon, the gifted comedienne, the abused wife, the President’s mistress. The slut. The martyr. So many, many Marilyns — one for every sexual or revenge fantasy under the sun and for every artist seeking an empty vessel into which they can pour Meaning. Andrew Dominik’s “Blonde” (in limited theatrical release now, on Netflix September 28, ** stars out of ****) boils all those Marilyns down to a single one — victim — and proceeds to beat us over the head with her, using cinema as his cudgel. There are ironies there, and they’re not pretty. Nor does Dominik intend them to be.

It’s interesting – and hardly a coincidence – that 2022 has given us biopics of the 20th Century’s two most irreducible cultural figures, Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe. In part, this is because a fresh generation requires tutoring. Elvis is almost a half century in the grave and Marilyn died sixty years ago last month; both exist for today’s kids and young adults as hazy pop demigods, divorced from their actual works and initial impact. They’re just … out there. Two students in a college course I teach on celebrity confessed to me a few years back that they hadn’t even realized Monroe was an actress, had appeared in movies. They knew her, of course, but they didn’t know why.

“Blonde” won’t clear the matter up. Like Baz Luhrmann’s “Elvis,” it’s a tangentially historical fantasia from a self-styled auteur, the difference being that Luhrmann is a showman and Dominik is a postmodernist professor in a hair shirt. (Only one of his movies has what one might generously call a sense of humor – 2012’s George V. Higgins adaptation “Killing Them Softly” – and, not coincidentally, it’s arguably the best thing he’s done.) “Blonde” lifts off from Joyce Carol Oates’ 700-page meditation on Monroe, a novel much praised when it came out 20 years ago, and it opens in Norma Jeane Mortenson’s childhood, where the little girl (Lily Fisher) is terrorized by a mentally unstable mother (a frightening Julianne Nicholson), almost burned to death, almost drowned, and shipped off to an orphanage, from which she hopes to be rescued by a father she has never known. The word “Daddy” is the emotional threnody that sounds throughout all 166 minutes of this movie, and by the end it lands like a curse.

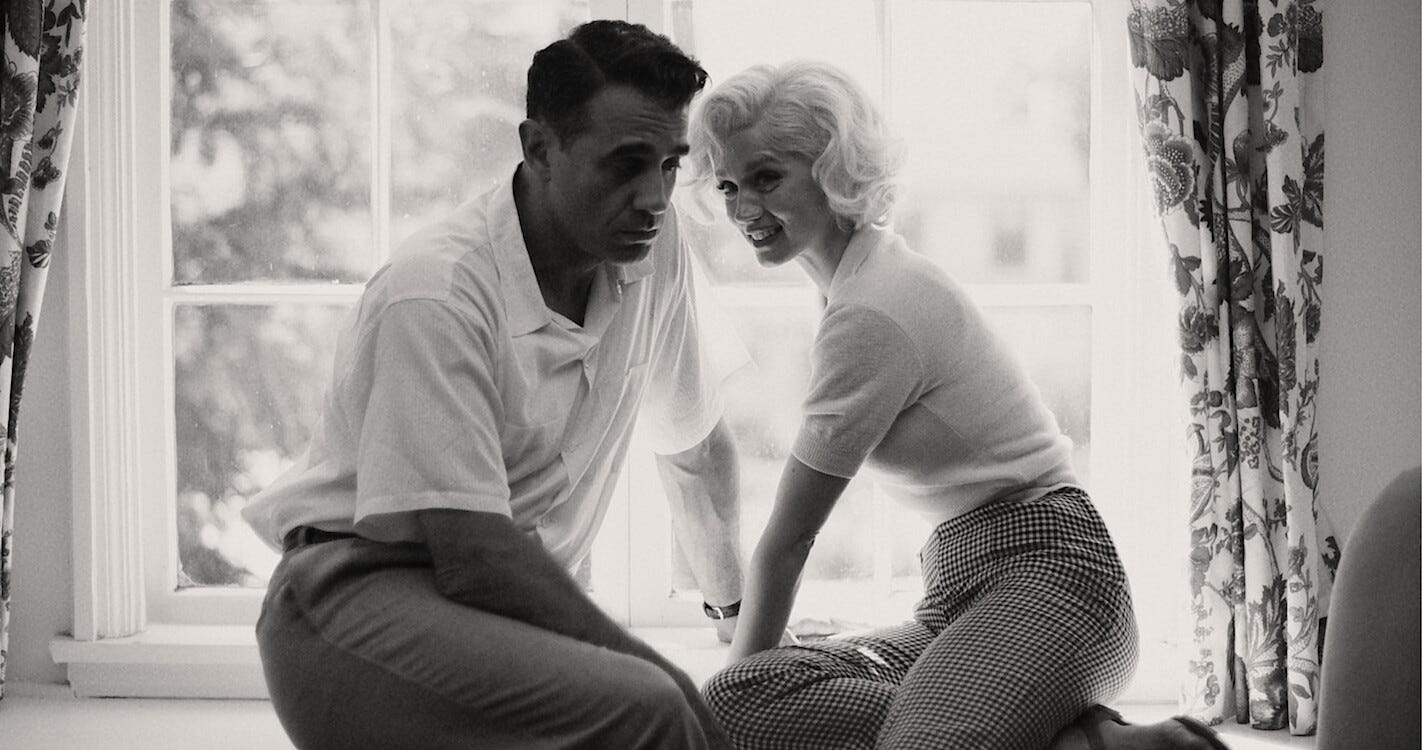

Once grown, Norma (Ana de Armas, above) moves to Hollywood and becomes a pin-up model; she’s sent to the Fox lot for an audition and is summarily raped by Darryl Zanuck (David Warshofsky, also above), the studio head’s generally acknowledged manner of introducing himself to starlets. The traumas pile up: Joe DiMaggio (Bobby Cannavale) beats her, the studio makes her get an abortion, second husband Arthur Miller (Adrien Brody) exploits her for art, the media exploits her for money. Only in a dreamy ménage à trois with two Hollywood nepotism babies – Cass Chaplin (Xavier Samuel) and Edward G. Robinson Jr. (Evan Williams) – is the star allowed a carnal and emotional happiness that isn’t rigged for abuse. They see her as her true self, Norma. They know that Marilyn doesn’t even exist.

All of this is flung at the audience in a pulsating anthill of cinematic styles, Dominik toggling between black-and-white and color film stock, imprisoning Monroe in narrow frame ratios before stranding her in widescreen, slowing down time and distorting the images in a Hollywood funhouse mirror. Norma isn’t the only one having a nervous breakdown; the movie is, too. The script underlines its dramatic parallels with a blunt Sharpie: Monroe auditions for “Don’t Bother To Knock” and marvels that it’s about “a mentally ill woman trying to kill a child.” And because Dominik finds the phenomenon of Marilyn to be supremely vulgar (as opposed to the actual woman), he uses vulgarity consciously to torture his heroine further and to lash out at us for our sins of lust and adoration. Will we get kitschy floating fetuses and an inside view of Marilyn Monroe’s birth canal? You bet. Will “Blonde” climax (you should pardon the expression) with a sequence of JFK brutally forcing the star to fellate him before an implied offscreen rape? It could be true, so that means it must be.

Not surprisingly, “Blonde” has already been reviled as hateful apostasy by audiences who just want to hear “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” and have a good cry; this includes probably 99 percent of the people who will encounter the movie on Netflix. Critics have been more nuanced, pro and con, because, hey, at least Andrew Dominik is trying something different. And yet – not. The beautiful movie star who was exploited to death has since been exploited by everyone who has told some version of the tale: Warhol, Norman Mailer, Elton John, Kim Kardashian, Madonna, Colin Clark of “My Week with Marilyn,” and now Dominik, who figures that by tormenting his Marilyn he can torment us – moviegoers, the media, an entire popular culture of rhapsody and rot. Does he include himself in the flagellation? Hard to say. Would that make it more acceptable? Intention counts for a lot. But so does artistic arrogance.

What about the actresses who play Monroe? Is representation ipso facto exploitation? I would hope that the more honest talents who have taken on the role – and they include Michelle Williams (“My Week With Marilyn”), Mira Sorvino and Ashley Judd (in the 1996 TV movie “Norma Jean and Marilyn”), and Poppy Montgomery (in a 2001 miniseries adaptation of Oates’ “Blonde”) – had some honest conversations with themselves and with their directors on the subject. It’s difficult enough to play the most recognizable movie star of all time and not seem like an impostor, not when so many sham Marilyns of every size, shape, and gender flood the culture. The Cuban-born actress Ana de Armas does her best and she’s not bad: She gets the voice most of the time, and the body language, but rarely Monroe’s half-narcotized glow. De Armas has a playfulness — see her scene-stealing turn in the most recent Bond movie — that has been purposefully doused here, and her Marilyn only comes alive as a person with agency and insights in the early scenes with Miller, which are so tender you feel as if you’ve wandered into another movie. Otherwise, “Blonde” is too busy stripping de Armas/Monroe down and beating them up to allow either woman even a little pleasure in their work.

At the end of the day, that’s what sticks in my craw: “Blonde” just isn’t all that interested in Monroe’s movies or, more generally speaking, what she did – only what she was (or what we think she was). And that ignores the palpable pleasure Norma Jeane Mortenson appeared to take in creating and inhabiting the pop edifice we know as Marilyn Monroe. “What needs to be reclaimed is her collaboration in and enjoyment of the business of self-reinvention,” I wrote about the actress in 2012. “Monroe remains more than a victim, more than a found object of helpless sexuality. Instead, she projects the struggle of the naturally sensual woman in a culture and an industry predisposed to distrust and control her. Her two best movies, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) and Some Like It Hot (1959), both put the matter bluntly. How can a woman get what she wants (money in Gentlemen, love in Some Like It Hot, security in either case) without being punished for it? More than that, why is a woman punished for it?”

“Blonde” never comes up with a convincing answer. It’s just hell-bent on assaulting us with her punishment.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how: