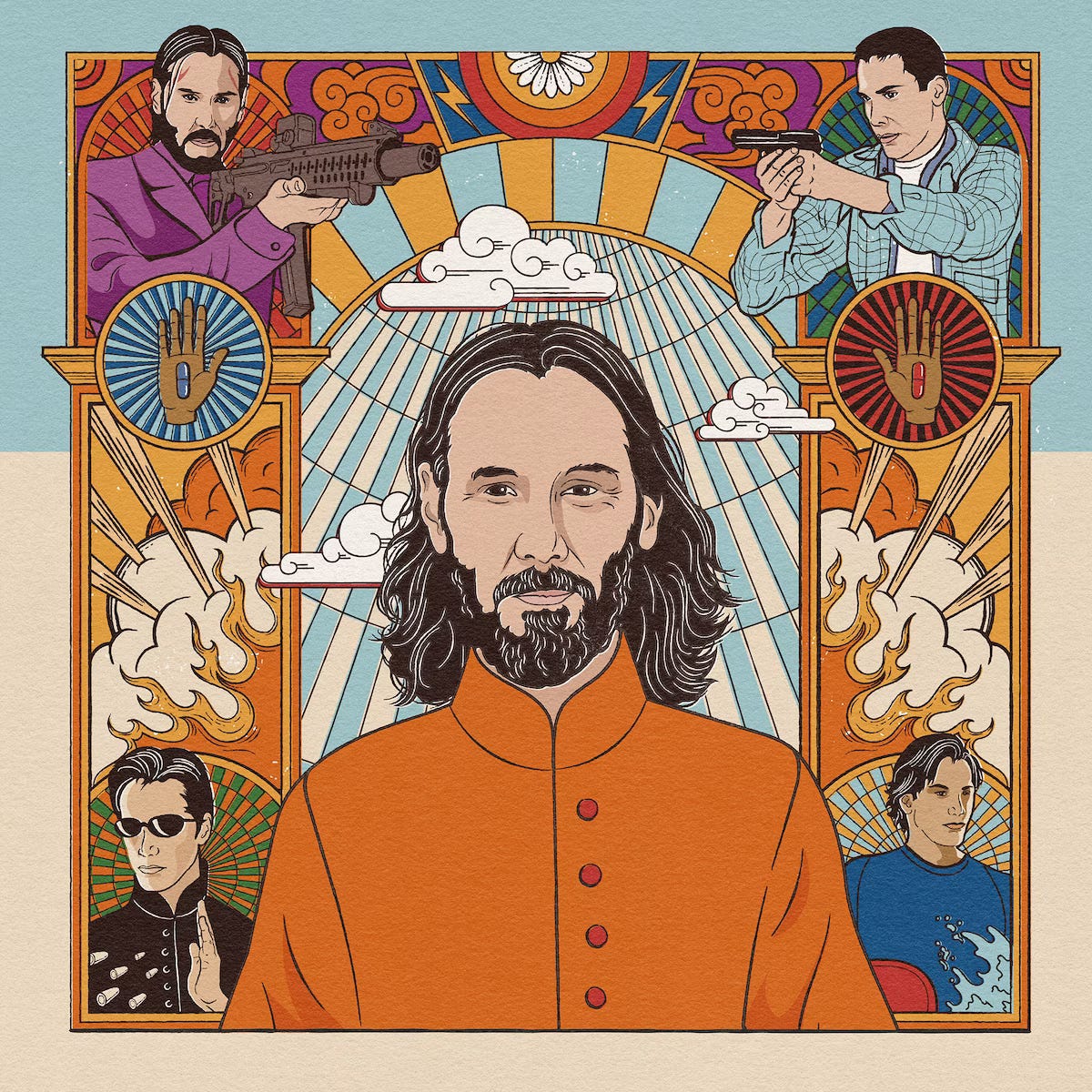

The full Keanu: Mellowest guy on the planet to onscreen killing machine

As ‘John Wick’ enters what might be its final chapter, Keanu Reeves remains appealingly hard to pin down. (Reprinted from the Washington Post)

I’m still gearing up for a return later this week, but as a bonus for paid subscribers who don’t subscribe to the Washington Post online, here’s the piece I wrote on Keanu Reeves for this past Sunday’s Arts section — I hope you enjoy it, because I certainly enjoyed writing it. TB

Reprinted from the Washington Post, March 26, 2023

Rare is the actor who gets to be a household name; rarer still are the ones with whom we’re on a first-name basis. Perhaps rarest of all is that star who so permeates popular culture — who seems so part and parcel of the air we breathe — that they start naming molecular compounds after him.

Ladies and gentlemen, meet the keanumycins, a group of recently discovered antimicrobial lipopeptides that ruthlessly kill harmful fungus the way the stoic assassin played by Keanu Reeves in the “John Wick” movies dispatches incoming villains. Why weren’t they named wickomycins? Even Reeves wondered as much in a Reddit posting, but his response to the question is such a compressed bouillon cube of all that is Keanu that it proves the researchers’ point and is worth quoting in full: “they should’ve called it John Wick … but that’s pretty cool … and surreal for me. But thanks, scientist people! Good luck, and thank you for helping us.”

There it all is: the earnestness, the goofy slacker-speak, the gracious and good-hearted honoring of other people’s good works. At the age of 58 and with nearly four decades of movies under his belt, Reeves has become beloved as an actor who doesn’t actually seem to act, a one-trick pony who can do just about anything — and an unstoppable on-screen killing machine who, in life, appears to be the mellowest guy on the planet. The man’s a Zen movie star, our National Dude, and with the release of the much-anticipated “John Wick: Chapter 4,” the affection in which a great many people hold him seems to be hitting a fresh peak.

A look back at a most paradoxical film career and public persona seems in order. What, truly, is the Tao of Keanu?

Over 40-plus movies, Reeves has been cast as the Buddha, the son of Satan, an alien emissary and the savior of mankind. He has played lovers, fighters, teenage idiots (“clown work,” he has approvingly called the Bill & Ted franchise), a naive French chevalier and a gay hustler based on Shakespeare’s Henry V. From one angle he’s the Gregory Peck of his era, modest and true; from another, he’s the black Lab of movie stars, faithful but maybe not the sharpest in the play group. There really is no fixed point by which to locate the man, which is definitely an aspect of the appeal. So, where do you start?

In Toronto, maybe, where Reeves was raised — he’s their National Dude, actually — and which is the source of the polite reserve that separates him from almost every other actor of his generation. You can still hear the Canada in that oddly formal Valley-speak, and you can sense it in the attentive way he listens, really listens, to other characters in his movies and to interviewers in the glossy magazine profiles devoted to him over the years. (This alone explains much of his appeal to women.)

After a rough-and-tumble upbringing, 22-year-old Reeves drove across the continent to Hollywood by himself in 1986 and had an agent within a week; it was the Brat Pack era, so who knew? (“I’ve just signed a new client, and I don’t even know if he can act,” his agent told a colleague, already tapping into a central aspect of the Reeves mythos.) Within a few months, he had a breakout role in “River’s Edge” as the one honorable teen pothead in a group dealing with a murdered peer. Go back and watch the movie: He’s already all there, the full Keanu.

Within a few years, Reeves had proved his range in the period film “Dangerous Liaisons” (1988), in “Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure” (1989), as jut-jawed surfer-lawman Johnny Utah in “Point Break” (1991, vaya con dios) and as the exiled Portland prince Scott Favor in “My Own Private Idaho” (1991), Gus Van Sant’s poetic meditation on street hustling and “Henry IV.” “My Own Private Idaho” crystallized Reeves’s bond with River Phoenix, an actor who always seemed to be seeking the core his friend already had. As Siddhartha Gautama, the young Buddha, Reeves was the best thing in Bernardo Bertolucci’s loopy “Little Buddha” (1993), an experience that seems to have stuck with the actor in ways that may have expanded his spiritual life and persona, in part because he has remained so private about it.

About that. Reeves has always gently but firmly drawn a curtain around his off-screen life, with an inborn awareness of the absurdities of fame — of how the Keanu we see is not the Keanu he is. (“I’m Mickey Mouse. They don’t know who’s inside the suit,” he told a Vanity Fair interviewer in 1995.) Public knowledge of certain losses — of Phoenix in 1993, of a stillborn child in 1999 and of the child’s mother, Jennifer Syme, in an auto accident two years later — and Reeves’s refusal to engage in public displays of grief have kept the culture at a sympathetic distance. We’re drawn to those celebrities who let it all hang out, but we don’t really take them to heart. The ones who withhold — not by choice or strategy but because they understand that the public circus isn’t where the things that matter happen — are those who get our respect.

In 1994 came “Speed” and an action role that was considered for Tom Cruise, Tom Hanks and Woody Harrelson before drastically changing Reeves’s image and bankability without changing who he seemed to be. That movie holds up fine, which is less than you can say for several that followed — Reeves’s overall hit-to-miss ratio is pretty bleak, actually — but the “Matrix” trilogy (1999-2003) confirmed his box-office power (and industry rep as a tireless trainer) while positioning the persona as a dreamy, ass-kicking revolutionary for reality. The Buddha of the Multiplex, or maybe just The One.

In the wake of that success, Reeves was able to do pretty much what he wanted for a while, including projects personal (Richard Linklater’s “A Scanner Darkly,” 2006) and mainstream (Nancy Meyers’s “Something’s Gotta Give,” 2003). My own favorite entry from this period is the swooning, lunkheaded romantic drama “The Lake House” (2006), in which Reeves and Sandra Bullock — the other black Lab of movie stars — somehow fall in love while living in the same house two years apart. There’s a magic mailbox involved; it’s really dumb and also really great, and the two stars never once condescend to the material.

Which brings us to the “John Wick” series, which puts this most serene of actors through insanely elaborate long-take ballets of on-screen ultraviolence while, again, allowing him to somehow remain himself. Reeves lets his age show for the films: lank-haired, unshaven and absolutely exhausted, Wick is the opposite of a rippled superhero just as the actor playing him is the antithesis of the Rock.

The movies — of which “John Wick: Chapter 4” might be the last — posit a global criminal bureaucracy that’s all-encompassing and a little bit ludicrous, with bespoke villain hotels and job titles out of a steampunk novel (The Adjudicator! The Harbinger!). They’re really postmodern samurai films, with Wick as a lone ronin facing an endless oncoming army, a notion that pulls so many facets of this unique star into one concentrated, irresistible figure. The movies would be far lesser vehicles with anyone else in the lead.

It would be nice if Reeves’s post-“Wick” filmography were … calmer. Maybe he can play a stalwart paleobiotechnologist who uncovers a strain of fungus-killing bacteria; it doesn’t have to attack New York City. As he nears his 60s — as he heads toward the status of cultural and cinematic elder — he may let the spiritual side that he has rarely alluded to in interviews take more precedence and affect his choice of projects. Or not. It may be the last thing “John Wick” fans and studio bean counters want to hear, but Reeves has never followed the fans. That’s why they follow him.

If you flip open a copy of the “Tao Te Ching,” the 2,400-year-old classic of Chinese philosophy, you may find any number of passages that seem applicable to this 21st-century Hollywood actor and to some of the characters he has played. “When you are content to be simply yourself and don’t compare or compete, everyone will respect you.” “The best fighter is never angry.” “He is free from self-display, and therefore he shines.” My favorite Keanu koan, and one that more movie stars would do well to heed, is this: “Act without expectation.”

Ty Burr is the author of the movie recommendation newsletter Ty Burr’s Watch List at tyburrswatchlist.substack.com.

Thoughts? Don’t hesitate to weigh in.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to pass it along to friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the management would be very grateful — here’s how.