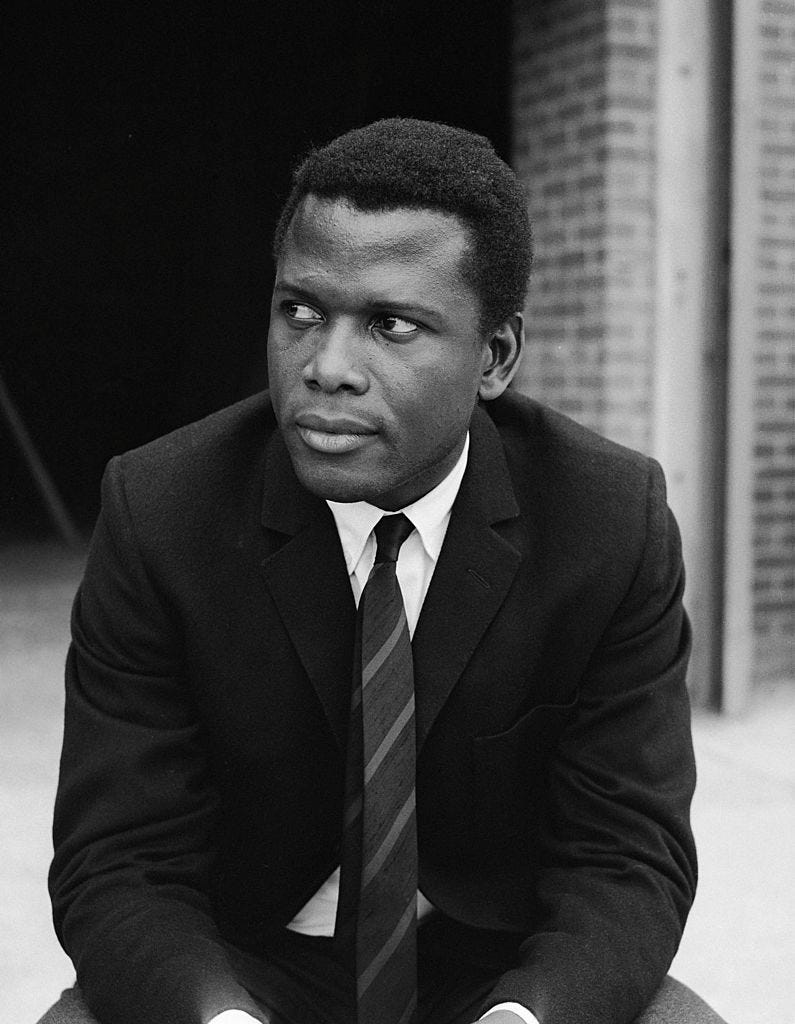

Sidney Poitier 1927-2022

The star who changed the movies and the role he had to play

It took decades for Sidney Poitier to be seen for who he was rather than what he meant. He was the first Black leading man in the movies, the first Black matinee idol, the first Black Oscar nominee for Best Actor (for 1958’s “The Defiant Ones”), and the first Black Best Actor winner (for 1963’s “Lilies of the Field”). He epitomized the movie star as social argument, and he was consciously used as such by white producers, screenwriters, and directors as Hollywood and America hurtled out of the post-WWII years into the Civil Rights era. As with Jackie Robinson, Poitier carried all of white society’s compromised notions of “Negro advancement” on his shoulders; both men had to be flawless, but Robinson “just” had to play ball. An actor wants to act, though, wants to be different people. For the first 20 years of his filmography, Sidney Poitier was – had to be – monolithic.

That makes it sound as if he had no hand in his own career, which couldn’t be further from the truth. But being all those Firsts threatens to put a man in a cramped box of passive nobility. When I show students the following clip from Poitier’s second film, 1950’s “No Way Out,” in which he plays a doctor at an inner-city hospital, they A) immediately grasp why he became a star and B) pick up how the racism portrayed in this scene had to be viewed through the eyes of a white doctor so that white audiences of the day would be able to condemn it.

Nearly two decades later, in 1967, Poitier was one of the most popular movie stars in the country, but he still had to be carefully framed for “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?,” in which he plays the fiancé of white Katharine Houghton. The opening sequence lets the two kiss – but only within the confines of a taxicab’s rearview mirror and only with the benevolent blessings of a white working-class cabbie.

See? If that guy has no problem with an interracial snog, how can you? Later, when Poitier’s character is introduced to his prospective mother-in-law, played by Katharine Hepburn, you get a sense of what the actor was up against.

He’s a doctor, he’s impeccably dressed, his wife and child died in a car accident – the movie doesn’t give the character any space to breathe, and it’s a tribute to Poitier’s genuine skill and warmth that he makes a human out of this plaster saint. “Dinner” was one of the year’s biggest hits and simultaneously derided by critics for its nervous liberal offering up of Dr. John Prentice as the Perfect Negro. The role grated on Poitier as well, but he understood the weight that he carried. In a 1967 New York Times profile titled “He Doesn’t Want to Be Sexless Sidney,” the actor said, “If the fabric of society were different, I would scream to high heaven to play villains. But I’ll be damned if I do that at this stage of the game. Not when there is only one Negro actor working in films with any degree of consistency. It’s a choice, a clear choice.”

Still, 1967 was also the year Poitier appeared in “To Sir, With Love,” forgoing a big paycheck for ten percent of the gross, a decision that made him rich when the film became an unexpected hit. More important, he starred in the year’s Best Picture winner, “In the Heat of the Night,” in which his Philadelphia police detective, Virgil Tibbs, gets slapped by a white plantation owner and immediately slaps him back. The scene drew cheers from Black audiences and gasps from white ones; Poitier finished the year as the top box-office star in the country.

By the end of the 1960s, when the door he had helped open had allowed others through – James Earl Jones, Ossie Davis, and Moses Gunn among them – you could sense Poitier relax into something like himself. Audiences had already had one measure of what he was capable of as an actor as early as “A Raisin in the Sun” (1961), in which Poitier recreated his 1959 stage role as the feckless Walter Lee Younger. One of his favorite performances, it allows the character to traverse a moral arc from self-centered ambition to racial pride in way that feels organic and unprogrammatic, and it gave Poitier a climactic speech that retains a trace of Broadway actorliness even as it’s imbued with genuine emotional power.

Poitier’s first film as a director was “Buck and the Preacher” (1972), which paired him with Harry Belafonte in a raucous, enjoyable Black western a half century before Netflix got around to “The Harder They Fall.” You can almost hear the star exhale with relief at not having to represent an entire people, just one idiosyncratic man, and while reviews at the time didn’t know what to make of the movie, it holds up extremely well as a racially conscious genre romp. By contrast, the three modern-dress comedies Poitier directed and starred in with Bill Cosby – “Uptown Saturday Night” (1974), “Let’s Do It Again” (1975), and “A Piece of the Action” (1977) – are very much period pieces now, although hardly without their loosey-goosey pleasures if you can get past Poitier’s co-star. And let us not forget – since everybody does – that the man directed Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor in “Stir Crazy” (1980).

After that, Poitier slipped gently and deservedly into the status of Legend. He wrote two memoirs, remained politically active, made films when he felt like it. He played Thurgood Marshall in a miniseries at the start of the 1990s and Nelson Mandela in a TV movie in 1997. He was given an honorary Academy Award in 2002, the same year that Denzel Washington became only the second Black Best Actor winner in Oscar history, 38 years after Poitier’s win. There’s progress and then there’s What’s taking so damn long?

Here’s a way to consider all that he accomplished and everything he couldn’t. Imagine what the movies would be like if Sidney Poitier hadn’t been there when the culture needed him. Now imagine what movies he might be making if he were just getting started today.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.