Those of you who follow me on social media may know that my wife and I have been dealing with a family health crisis in recent weeks: Her father, my father-in-law, went voluntarily into hospice care early this month and passed away last Sunday. He was 91, in full possession of his faculties but in deteriorating health, and he got to spend a final week with his wife, three daughters, three sons-in-law, and eight grandchildren telling him how much he was loved. It was, as these things go, a good death. That doesn’t make his leaving any easier.

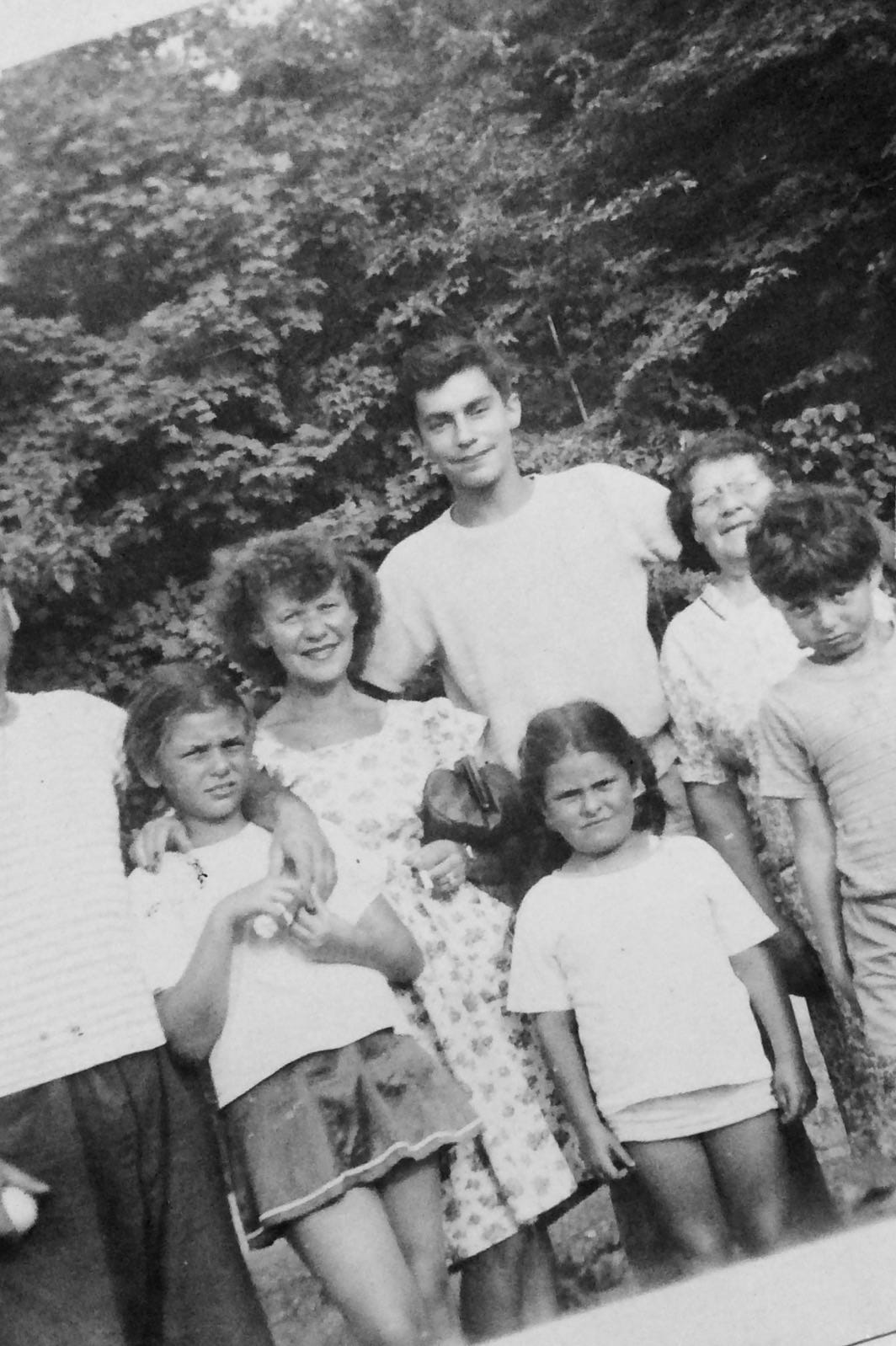

I don’t know why I’m writing about him in this space; probably just to hold on to him a little longer. My father-in-law and I had a movie connection, which I’ll talk about in a bit and which had a satisfying and emotional closure last week, but, honestly, while he lived a full and exemplary life and touched many people, he wasn’t the kind of hero who gets a full-page obit in the Times. (Family members have requested I keep his identity private for this post, and I’m respecting that.) The son and grandson of Jewish immigrants, he grew up in Brooklyn during the Depression and early years of World War II, went to medical school, specialized in internal medicine and gastroenterology, and took over his father’s small-town practice in New York, working both in an office adjoining his house and at the local hospital, where he practiced for many years and where he instituted programs in medical ethics and quality control. He married my mother-in-law and they had three daughters. He took them on cruise ships and European tours. In his 40s, he bought a boat and took up sailing. In 1991, at the age of 60, he retired and spent the next 30 years happily traveling the world and playing golf at a country club community in Florida. On paper, there’s not a lot to separate him from other men of his time, place, and profession.

In person, as my wife and I and other family members agreed, he was a kind of Buddha. The ordinary kind – the sort who passes through life with a quiet smile and even composure, doing good works and acting with selfless compassion not because it’s how he was taught but because that’s who he is. In their reminiscences at my father-in-law’s memorial service on Wednesday, all three daughters recalled a childhood of people streaming up to their father on the streets of their hometown with thanks and symptoms and the reverence you give someone who you know actually cares. He was patient-centric at a time when that marked him as an oddity. He was one of the first doctors in his area to reach out to and treat those suffering and dying from AIDS.

As someone who lost a father at an early age and looked on and off for others to fill the bill, I found my father-in-law to be not a substitute but something better – an example of how to be in the world. He didn’t hand out life advice unless he was asked, and he had no interest in playacting the patriarch. He wasn’t performatively macho; I think he got enough of that from his own father, and it wore him out. As I wrote on Facebook this week, he had simple pleasures – music, food, sailing, golf, history – but he enjoyed them profoundly, and in that there was a lesson, too. In Zen Buddhism, there’s a series of drawings and poems known as the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures that illustrates the search for and attainment of enlightenment; in the tenth picture, after seeking, taming, and riding the Ox, and after transcending reality and vanishing into emptiness, the practitioner returns to Earth as just another human being, “mingling with the people of the world,” his illumination and compassion invisible perhaps even to himself but embodied within. That’s how my father-in-law seemed to me: Someone who had figured it out so thoroughly that he carried it around inside him, forgotten but functioning.

He adored his family, and they responded in kind. Strangers often mistook him for the movie star Martin Landau, and sometimes, if he was hurrying from one place to another, my father-in-law would accept their compliments on his performance in “North by Northwest” or “Mission: Impossible.” He and I got along in a quiet way. I have a risotto recipe that was comfort food to him, and it was a comfort for me to make it more than once in his final weeks. And there were the movies. As a film critic with an annual Ten Best list, I’d arrive for year-end visits in Florida proffering a stack of DVDs as a gesture of filial respect, and he would disappear into his recliner for days on end, voraciously consuming classy dramas, gory horror films, avant-garde indies – any and everything. His responses were unguided by critical approval or social media buzz; he liked what he liked and didn’t like what he didn’t like, and there was no predicting which would be which. His tastes were neither art-house elitist or multiplex mass-appeal; they were simply his and, as such, adventurous and open to engagement from all quarters. The good ones he marveled at, and his marveling was a marvel in itself.

The week my father-in-law died, after the grandkids had flown back to their homes and he was getting impatient for the end, we asked if he wanted to listen to any favorite music or watch a movie that he remembered fondly. That led to a welcome revisit with Mel Brooks’ “Blazing Saddles” and a hospice-care nurse assistant genuinely bamboozled by what she saw coming off the screen. And then, out of nowhere, he asked to see a movie starring Joel McCrea, the handsome, likeable star of comedies and westerns and dramas from the 1930s through the 1960s. Any particular one? He had no suggestions; he was already beginning the long fade and maybe this was just the tickle of nostalgia or a bubble of memory from a moviegoing youth. After some consultation, we put on 1942’s “The More The Merrier,” a screwball comedy set in a crowded wartime Washington D.C., in which McCrea and Jean Arthur and foxy old Charles Coburn share an apartment and McCrea and Arthur fall in love.

I hadn’t seen it in decades, my wife hadn’t seen it at all, and I never learned whether my father-in-law had it under his belt prior to our renting it on Amazon Prime. No matter: The movie holds up beautifully – it’s hilarious and sexy and romantic as hell, and we all sat there giggling and gasping as if it had been released yesterday.

It was the last time I heard him laugh, and I’m holding on to the sound of that laughter as a way of saying goodbye. Home is the sailor, home from the sea.

If this struck a chord with you and you’d like to share it, please feel free to do so.

I normally write about movies and popular culture, and if you’d like to read more on those topics, you can do so here: