Playlist Madness: Byrds v. Fairport

With further thoughts on the egotistical futility of music management.

As January has been the traditional potter’s field for new movie releases – the place where studios go to bury their halt, lame, and blind as anonymously as possible – and because I’m gearing up to go to the Sundance Film Festival next week, I’m taking the day off from movies and instead detouring readers down a musical cul-de-sac. True, this is an excuse to scratch my playlist itch, which has gone mostly unscratched in the years since my kids have grown and left the house.

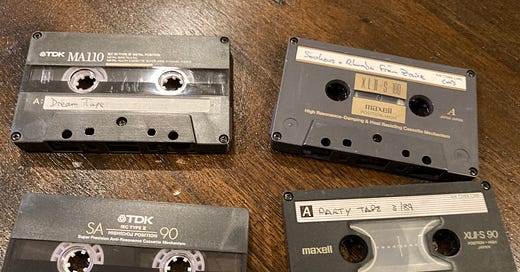

Oh, the playlist itch – do yourself a favor, reader, and head for the hills now. Born way back in the tape cassette days, when swains of both genders would laboriously cue up vinyl tracks on their turntables, hit the REC button, and tremblingly press the C-90 results into the hands of their beloveds – usually with the accompanying note “If you truly want to know me” – the mixtape/playlist took a series of quantum leaps with the advent of burnable CDs, then MP3s, iTunes, and Spotify.

Playlists have always been the province of sentimentalists and stalkers, dance party alpha-males, completists, historians, OCD list-makers. And strainingly hip dads, of course, which has been my own shameless sub-species in the genus. I am a man who once sent his younger child to school with a home-curated “History of Post-Punk” CD to play in their music class; I am also the dad who made a Philadelphia Soul playlist so that my children could properly understand the cultural transition from Motown to Disco. Worse – so much worse – I have burned playlist CDs for various nieces and nephews and even my kids’ friends if they made the mistake of expressing the vaguest interest in what was playing on our stereo during a playdate. I am pleased to report that, so far as I know, those playlists went unheard and never remarked upon — the only proper response when a random adult tries to dump his generation’s arcana on you. Have you ever seen that Onion article about the Cool Dad who destroys his daughter’s generational taste? That was written about me.

The appearance a decade or so ago of streaming platforms like Spotify and Tidal really unleashed my inner Kraken. I have made playlists – why, yes, I will provide links – devoted to the late downtown avant-disco martyr Arthur Russell and to Miles Davis’s kiss-off albums to his Prestige Records contract; to dad-rock warhorses the Beatles, Stones, Kinks, and Who; and to obscurities like the ancient outsider-folkie Michael Hurley, British instrumental pastoralists The Penguin Café Orchestra, and the delightful early-2000s electronic duo Lemon Jelly. I have made a playlist commemorating my teenage years and a playlist of the songs I want played at my funeral. Somewhere locked inside my head is a playlist of every piece of music I have ever listened to, a playlist that’s as long as life itself and that somehow functions as a more orderly simulacrum of life – a notion that Borges might sign off on, or Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman), the playwright re-staging his own existence in real time in Charlie Kaufman’s “Synecdoche, New York.”

A fair question or three: Who am I making these playlists for? Who am I trying to convince? What’s the urge being slaked by all this sorting and stacking, the endless recombination of infinite musical possibilities? Is there a Platonic playlist I haven’t yet discovered, a final combination of songs that will tease the tumblers loose and unlock some final mystery of being? And will I disappear upon listening to it, my atoms redistributed among the notes? Or are playlists, in the end, just advertisements for ourselves – little sonic samples of ego? If you truly want to know me. Well, who the hell wants to know?

One of the small but welcome shards of wisdom that comes with getting older and learning not to give a tinker’s damn about a lot of things is the acceptance that you – by which I mean me – have always and only been making playlists for yourself, regardless of who they’ve been superficially meant for. They serve as a useful mnemonic and a personal history, a way to conjure up specific times and nano-moments of one’s past – the smells of certain days, shades of particular sunlights, remembered joys and despairs that mean nothing to anyone but the person who experienced them. Sure, playlists are fun, too. But sometimes, if you’re lucky, you put two things together and a third thing shakes loose.

That’s 700 words of preamble to the simple fact that I was thinking not long ago about folk rock – a genre that the music trades and streaming playlists now call “Americana”– and how it got started a half century ago. More particularly, how two musical groups that in the 1960s begat the two chief strains of folk rock, The Byrds in America and Fairport Convention in England, created related but distinct styles from the same three buckets of material: traditional folk sources, original compositions, and a ton of Bob Dylan covers. With those similar origins in mind, what would these two bands’ songs sound like when put next to each other? What a stupid idea. Let’s find out.

It bears remembering that before The Byrds had a hit with Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” – their debut single, released on April 12, 1965 – folk music and rock ‘n’ roll were two mutually opposed camps. The folkies thought the rockers were teenyboppers or thugs and the rockers thought the folkies were wimps. One month previously Dylan had released his first set of electric songs as Side A of “Bringing It All Back Home,” so he gets the nod for birthing folk rock. But The Byrds commercialized it with a tight, professional studio sound that did as much to bring Dylan to the masses as his own “Like a Rolling Stone,” which went to No. 2 on the Billboard charts three months later. The band’s influence was immediate and lasting, inaugurating the L.A. rock scene, a raft of folk rock imitators, and a jingle-jangle 12-string guitar sound that George Harrison, among others, immediately picked up on (listen to “If I Needed Someone,” which nicks the chords and feel of “The Bells of Rhymney”) and that has sparkled down the years to The Feelies, R.E.M., and many others. As for The Byrds’ vocal harmonies, themselves influenced by the Beatles, founding member David Crosby would take them to the bank when he joined up with Stephen Stills and Graham Nash a few years later.

If The Byrds were slick, Fairport Convention was rough and rowdy – an inspired pub band with a pair of once-in-a-lifetime talents in vocalist Sandy Denny and master guitarist Richard Thompson. The Byrds launched a thousand singles acts; Fairport, by contrast, kicked off the roots movement, the electric cèilidh, and served as an important genetic strand of the jam-band genre. They never made it big in the US (although Denny’s signature tune “Who Knows Where the Time Goes” quickly became and remains a standard, and generations of Led Zeppelin fans know her as the Faerie Valkyrie singing back-up on Zep’s “The Battle of Evermore”) and they never achieved Top 40 success in England. But the Fairport’s influence was, like The Byrds’, deep and lasting. An entire school of British folk rock sprang up to pillage the British medieval songbook in the group‘s wake, including Steeleye Span, Renaissance, and Jethro Tull, the last maligned by everybody except teenage boys of the early ‘70s (ahem), who adored Tull because the lead singer stood on one leg while playing the flute.

The Byrds and Fairport had other qualities in common: Deep benches of songwriting talent (respectively, Crosby, Gene Clark, and Jim/Roger McGuinn; Thompson, Denny, and Ashley Hutchings) combined with a remarkable inability to hold on to key bandmembers for very long. The various personnel shifts, ousters, and assorted melodramas are enough for an entire grove of rock family trees, with The Byrds alone seeding Crosby, Stills, and Nash, The Flying Burrito Brothers, Souther-Hillman-Furay, and a generation of bluegrass musicians influenced by later member Clarence White.

The Byrds, too, brokered more than folk rock. The Coltrane-influenced “Eight Miles High” single and the album it appeared on, 1966’s “Fifth Dimension,” introduced psychedelic rock into the commercial lexicon, and when the Southern-born, Harvard-educated bad-boy genius Gram Parsons joined the band in 1968, the result was the brilliant “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” album and the creation of country rock – a fusion of two genres even further apart than folk and rock had been. (The kids thought country music was for murderous rednecks; the C&W crowd thought the kids were Commie freaks.) From that one record rose Pure Prairie League, Poco, New Riders of the Purple Sage, and you can thank or blame “Sweetheart” for The Eagles, too. But in 1968, the Columbia Records marketing department was so bolluxed that their radio ads literally tried to argue listeners into buying the album.

Fairport Convention quickly lost Sandy Denny to a solo career and a tragically early death after a fall down a flight of stairs; with the departure of Richard Thompson in 1971 to follow his own exemplary, eccentric, and still ongoing musical path, the band lost a lot of the dark magic that separated it from its RenFaire imitators. Certainly the genuine madness was gone that could be heard in the long instrumental freak-outs that backended Fairport’s versions of traditional tunes. Of these, none is more majestic than “A Sailor’s Life,” from 1969’s “Unhalfbricking” – an 11-minute adaptation of a folk song first published in the 18th century that starts with Denny singing into a formless void and slow-builds to an astonishing maelstrom of sound, Thompson’s guitar and Dave Swarbrick’s violin trading blows like ships exchanging cannon-fire in a raging gale. The All Music website describes “A Sailor’s Life” as “a song that just makes the listener ‘white out’ inside, mouth open, when it’s over,” and it’s possible/probable that Jimmy Page gave it a close listen when composing the similarly structured “Stairway To Heaven.”

But there are surprises from both groups throughout this playlist: David Crosby’s “Lady Friend,” a failed single that nevertheless sounds like a cathedral of bells collapsing in ecstasy; Sandy Denny’s “She Moves Through The Fair,” which could be a lost classic from Haight-Ashbury’s Summer of Love; a traditional tune from the Fairports, “Nottamun Town,” whose melody Bob Dylan had already pilfered for “Masters of War”; and two versions of “The Ballad of Easy Rider” that illustrate the difference between The Byrds (compact, string-laden, radio-friendly) and Fairport Convention (shaggy, stately, soulful).

At the end of the day, what did I get out of making this playlist? The realization that as much as I have always loved the streamlined ear-candy of The Byrds – and as much as “Sweetheart Of The Rodeo” ranks high in my personal pantheon – the rough edges of Fairport Convention have always haunted me longer and more deeply. At their best, they coaxed the darkness and the mystery, the sorrow and carousing, from England’s past and brought it timelessly back to life.

And you? What did you get out of this playlist? There will not be a test. You don’t even have to listen to it. And if it makes you feel better, know that my kids started making me playlists once they got to college, and I have to tell you — their taste is a lot better than mine.

Thanks for going with me down this rabbit hole. As a treat to readers who’ve made it this far, here’s a rare recording of Richard Thompson live, joined by Talking Heads’ David Byrne, in a rendition of Thompson’s devilish “I Feel So Good,” at the Town Crier in Pawling, NY, on March 7, 1991.

How many playlists have you made? Feel free to share ‘em below!

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, by all means pass it along to others.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be eternally grateful — here’s the button.

You can give a paid Watch List gift subscription to your friends —

Or refer friends to the Watch List and get credit for new subscribers. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll:

Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

Get a 6 month comp for 25 referrals. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

There’s a leaderboard where you can track your shares. To learn more, check out Substack’s FAQ.