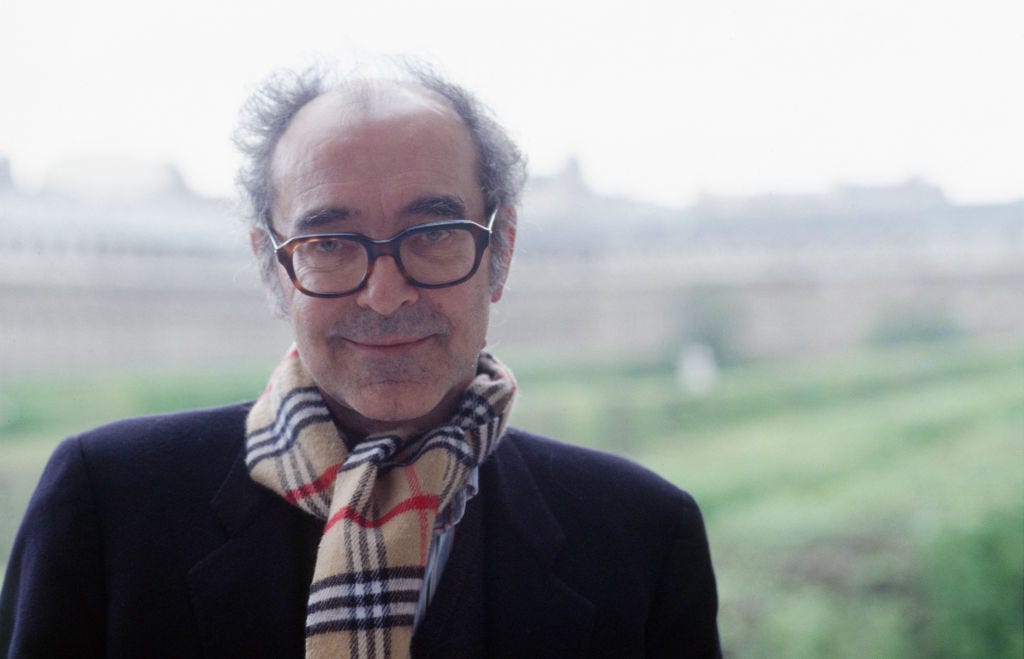

Jean-Luc Godard 1930-2022

The French New Wave director was to movies as Picasso was to art, Joyce to literature, and Dylan to popular music.

The world feels a little emptier, more monochrome, when you lose a member of your personal pantheon. By “personal,” I mean a cultural figure who altered my own inner landscape and arguably my destiny; who taught me how to see in different colors and in more dimensions than I’d known were there. Jean-luc Godard, who died yesterday at 91, was the filmmaker through whom I finally understood that art was more powerful, could be a vehicle for greater profundity, when its meanings hovered just out of the reach of words.

This isn’t just about learning to not be afraid of “difficult” cinema, although there’s that; coming to Godard in college after an adolescence of comfortable old-movie worship was for me a discombobulating and initially scary experience, prompting all sorts of youthful insecurities about fitting in and figuring stuff out. And I knew I was standing on the border of a new country: How are you going to keep them down on the farm after they’ve seen “Vivre Sa Vie”?

There are a few films that you can point to and argue that they broke the history of movies in two. Hitchcock’s “Psycho” is one, the dividing line between the cinema of sentimentality and the cinema of sensation in which we still live. Another – perhaps the other – is “Breathless,” which is to classical narrative cinema as Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” is to figurative art: A breakdown and reordering of the medium and the senses. A genre film cut up and thrown into the air; a love letter to Bogart and Jean Seberg and America, and also an insistence on Paris at the precise moment it was captured by Raoul Coutard’s camera. It’s no coincidence that “Psycho” and “Breathless” both came out in 1960, and both pointed the way toward the future, or futures. “Breathless” was the result of Godard’s absorption of Golden Age American and French filmmaking, his taking its DNA into himself and spitting it back onto the canvas recombined with love and anarchy. In so doing, he forced a new generation of American filmmakers to interpret their own legacy in a fresh light. Without him, no New Hollywood, no independent film, no garage or guerilla moviemaking, and certainly no cinema of the intellect. Godard moved film from the heart to the head – and, yes, sometimes he could put that head up his ass.

But, no, that’s not entirely true, because what makes Godard’s magnificent run of movies in the 1960s isn’t their pretensions but their passion – for art, for life, and for the ridiculous and lifelong task of trying to separate one from the other. For women, too, and for books, and of course for the movies, which for Godard is where it always came back to, because the movies were life with the dull bits missing, and if you put the dull bits back in, would it exalt them and make life seem more like a movie? The famous scene in “Masculin Feminin” (1966) commemorates an inflection point of disenchantment, perhaps the first step toward the Marxist/Maoist collectivist cinema that obsessed Godard in the years after the near revolutions of 1968. Paul (Jean-Pierre Léaud) goes to a movie with his girlfriend and experiences a larger disenchantment: “The screen would light up, and we’d feel a thrill. But Madeleine and I were usually disappointed. The images were dated and jumpy. Marilyn Monroe had aged badly. We felt sad. It wasn’t the movie of our dreams. It wasn’t the total film we carried inside ourselves. That film we would have liked to make, or more secretly, no doubt, the film we wanted to live.”

This was a young person’s cinema, obviously, although the movies hold up today, as embers around which to warm memories of youth and as continued inspirations to new generations of directors. And Godard never went away, although the culture receded almost entirely from him as his brand of personal cinema sank from view beneath an age of blockbusters. He remained the playful demon imp in the projector, goading the Catholics with an image of the Virgin Mary as a modern high school girl (“Hail Mary,” 1985 – a wonderful film and I’ll never forget the nun outside the movie theater angrily assuring me as I walked in that I’d be going to Hell), deconstructing 3D cinema in “Goodbye to Language” (2014), and returning to his worshipful, encyclopedic Cinémathéque roots with the epic “L’Histoire(s) du Cinema,” a four-hour documentary masterpiece that isn’t so much a history of the movies as a history of how we watch ourselves through the movies.

Godard mattered as a critic, too, of course. With his work in Cahiers du Cinema in the 1950s, alongside the other movie-besotted boys (and one woman) who’d go on to make up the French New Wave, he turned writing about film from reviewing to investigating and from prose into a personal, sometimes obscure poetry. (It’s often been said – by me, anyway – that Godard in the 1960s put cinema through the same changes Bob Dylan was visiting on popular music at the time, but his influence on an incoming generation of film critics was equally seismic.) And he insisted, increasingly and above all, that the movies were, like life, inseparable from politics and from the never-ending battle against the forces of authoritarianism and state-sponsored cruelty. As recent a film as “Notre Musique” (2004) refracted the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through the circles of Dante’s “Divine Comedy.”

The early films, too, remain as uncompromisingly radical as ever, even before the sloganeering of the Dziga-Vertov years. I hold most of them very close to my heart, especially “Vivre Sa Vie” (1962); the glorious “Contempt” (1963) in which Godard bites Hollywood’s proffered hand like a junkyard dog; “Two or Three Things I Know About Her” (1967), which finds the universe in a cup of coffee –

— and “Alphaville” (1965), a sci-fi future shot in the soulless architectural spaces of contemporary Paris. But the one that rocked my world and opened my mind like a cinematic satori was and remains 1965’s “Pierrot le Fou,” a widescreen Technicolor Cubist masterpiece in which Jean-Paul Belmondo flees his life and wife with the babysitter, played by Godard’s muse Anna Karina, into a dreamtime South of France. There crime movies and political protest intertwine, along with a charming musical number and the gnawing certainty that men will never, ever understand what women want or need or are even about. “Pierrot” is, among other things, a love letter to Karina, with whom Godard was then breaking up, and it’s among other things a suicide note to the idea that love could ever be put on camera in a way that might change things in the real world. And still we try, which is why Godard brings on the grizzled American director Samuel Fuller to explain that film is simply a battleground for our emotions, no more and no less.

And still we fail, which is why the camera drifts out over the sea at the end, following the smoke of an exploded overloaded mind, and contemplates eternity.

He’s gone now at 91, forgotten by the mainstream that once knew him as a visionary and a gadfly and now only senses him as an influence. You could say that the movies moved beyond Jean-Luc Godard after the 1960s. But you could also say we fell behind. It’s not too late to catch up.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how: