Is "Jeanne Dielman" the Greatest Movie of All Time?

Doesn't matter. What counts is that we're talking about it.

Every decade since 1952, the British Film Institute’s magazine Sight and Sound has polled film critics, filmmakers, curators, academics, and others on what they consider the “greatest films of all time.” The result has been a rarity in this onrushing, list-obsessed popular culture: A Top 100 (and a Top Ten, which is what most people pay attention to) that provides a long view of shifts in tastes, fashion, subjects, and filmmaking styles. As you’d expect, there’s always controversy. The dethroning of decades-long No. 1 choice “Citizen Kane” by “Vertigo” in 2012 occasioned much handwringing from staunch upholders of tradition and/or those who thought Hitchcock’s most achingly personal meta-melodrama was too weird or too boring. And when the 2022 S&S poll results came out late last week, a lot of people plain lost their minds. The top choice? Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” (1975, above), a three-and-a-half hour Belgian film that the average moviegoer has never heard of and that would (and likely will) give the average moviegoer fits if and when they watch it. What gives? Where’s “The Godfather”? (at No. 12.) Where’s “Casablanca”? (No. 63.) Where’s “The Shawshank Redemption”? (On some other list.)

A number of things to note.

The poll unquestionably reflects the ways in which the Internet and streaming video have made available a vast variety and history of cinema, opening up the canon in ways unthinkable by the standards of eighty years ago. In 1952, you read the list and wondered if you would ever get to see some of these movies. In 2022, you can screen the majority of the S&S 100 right now, today.

There were 63 people polled in 1952. in 2022, there were 1,639, almost double the number of the 2012 edition.

That very first group of respondents was made up of film critics, mostly men, all white; in 2022, a scrupulously diverse range of professions, genders, and ethnicities was polled. The results reflect as much: In 2012, there were two films by women filmmakers in the Top 100; in 2022, there are 11, with one in the top spot for the first time ever. One Black filmmaker was represented in 2012; there are seven in 2022. Some critics consider this a caving in to “woke culture.” I prefer to think of it as a long-overdue widening of the lens.

The bottom line is that those polled are people who know about film, care about film, and have in one way or another made film the center of their lives. The Sight and Sound poll is not a popularity contest. (For that, go to IMDb.) It’s a considered list of what, in the long view, are the 100 films that have made the most lasting contribution to and had the most profound effects on the medium and the surrounding culture(s), high and low. You are, of course, encouraged to argue.

That contribution and those effects can take years to reveal themselves – a far longer time span than any insta-ranking on Buzzfeed. Again, that is the value of this particular list. The appearance of a new film in or atop the S&S Top Ten is usually the tip of an iceberg that’s been gathering mass for years. In this case, it has taken almost a half century for “Jeanne Dielman” to be recognized as a hinge-point in how movies tell stories, present women, and convey ideas. In 2012, the film came in at #38; in 2002, it wasn’t on the list at all. But it has been rising for decades in the conversation of people with their ear to the ground of international cinema, feminist filmmaking, and non-traditional narrative. More to the point, the radical nature of “Jeanne Dielman” has, over time, become so absorbed by the culture that you have almost certainly felt its effects even if you’ve never heard of the film. (Among other things, the movie established the long take as a provocation and an argument.)

Okay, the film itself: “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” is an examination of the title character (played by Delphine Seyrig), an expressionless middle-aged single mother whose life is a succession of dreary tasks that we watch in uninterrupted single takes. She cooks, she cleans, she makes meatloaf, she peels potatoes, she feeds her impassive teenage son (Jan Decorte), and – oh, yes – she turns tricks every afternoon to subsidize her meager existence. All of this is presented in as close to real time as possible, throwing the audience back on itself and forcing them to either flee in discomfort or think hard about what they are watching. It’s a work of purposeful anti-entertainment, interrogating a woman’s place in a society constructed by men. It’s also a masterpiece of empathy and rage, as Jeanne’s daily routine begins to unwind over the course of three days, with little hiccups, bits of surreal static, in her unthinking stations of the cross, until the film itself seems to buckle with a sudden act of violence that, in retrospect, we realize has been coming for 200 minutes.

”Jeanne Dielman” is a landmark in slow cinema; you have to ratchet your metabolism down if you’re going to meet it halfway. It also forces one to consider the nature of film as part of a system of narrative that confines women within the shot language of what critic Laura Mulvey popularized as “the male gaze” in a seminal essay that came out in 1975 (not at all coincidentally the year of the movie’s release). The frame itself is a prison in “Jeanne Dielman,” and our realization of that – and our place in relation to that frame – is part of what makes the film a radical reordering of the cinematic senses.

Mulvey has written a new article on the BFI’s website on the occasion of the movie’s ascension to the top of the Sight and Sound list; I highly recommend reading it before or after watching “Jeanne Dielman” itself on the Criterion Channel (where it nestles among other Chantal Akerman films; the heartbreaking “News From Home,” from 1976, is especially recommended), on HBO Max, or for a small rental fee on Amazon and Apple TV. Those wanting a deeper dive behind the scenes of this maddening, fascinating film can watch a making-of documentary, “Autour de Jeanne Dielman,” on Vimeo. (Don’t forget to turn on the subtitles.) However you approach it, it is a work to be reckoned with.

Here's the rest of the Sight and Sound Top 10.

2. Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958)

3. Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941)

4. Tokyo Story (Ozu, 1953)

5. In the Mood for Love (Wong, 2000)

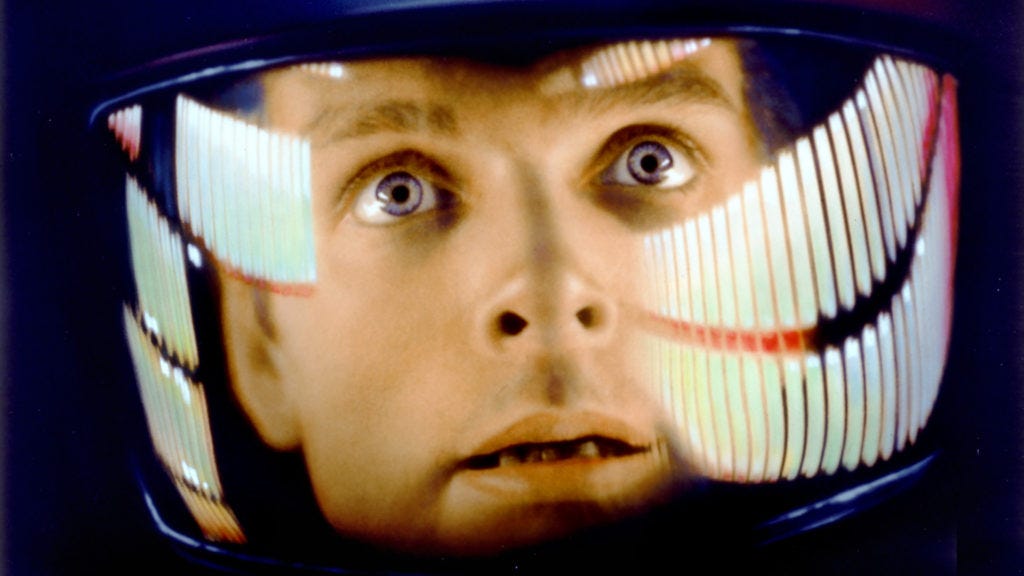

6. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968, above)

7. Beau Travail (Denis, 1998)

8. Mulholland Dr. (Lynch, 2001)

9. Man with a Movie Camera (Vertov, 1929)

10. Singin' in the Rain (Kelly/Donen, 1951)

And, for the record, here are the ten films I submitted to the poll. We weren’t asked to rank them, but since 11 years of making lists for Entertainment Weekly is hard to get out of your system, I went ahead and did it anyway. As above, you are free and encouraged to argue.

1. Late Spring (Ozu, 1949)

2. The Godfather (Coppola, 1972)

3. Celine and Julie Go Boating (Rivette, 1974)

4. Au Hasard Balthazar (Bresson, 1966)

5. Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958)

6. Sherlock Jr. (Keaton, 1924)

7. Where is the Friend’s House? (Kiarostami, 1987, above)

8. Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017)

9. Lola Montès (Ophuls, 1955)

Mulholland Dr. (Lynch, 2001)

Thoughts? Comments? Don’t hesitate to share.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to pass it along to friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

One more thing: The holidays are coming, and what better gift for the movie-besotted loved one on your list than a year’s subscription to Ty Burr’s Watch List?