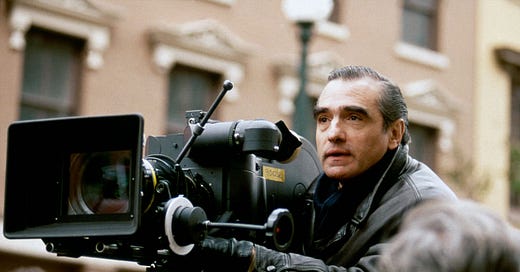

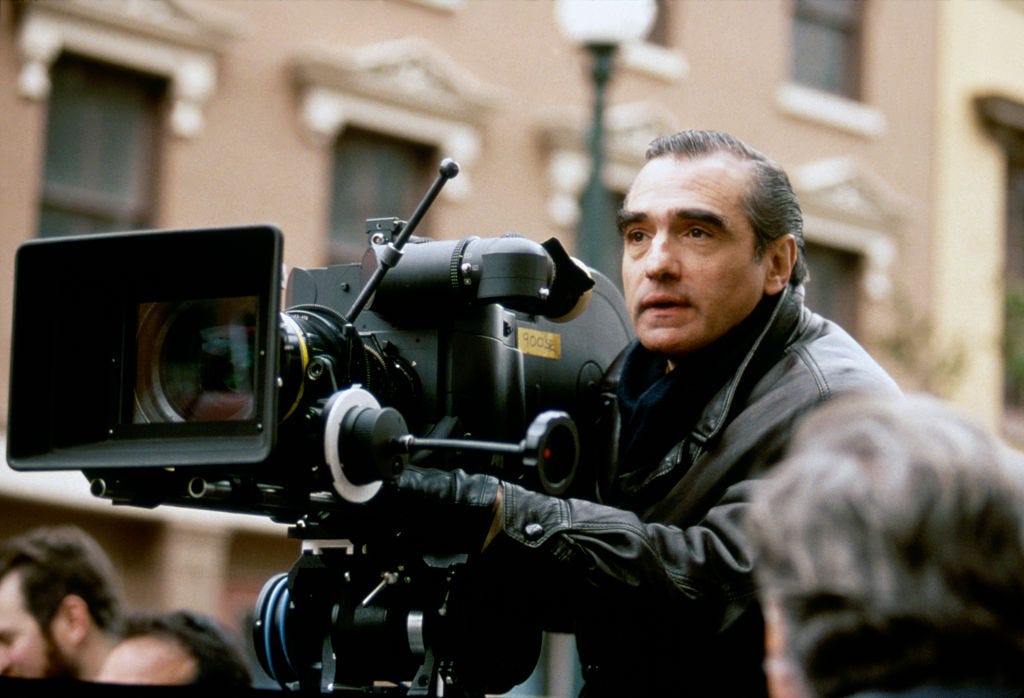

Tomorrow is Martin Scorsese’s birthday – the living conscience of American film turns 80. (Correction, the living conscience of global film; check out the director’s personally curated DVD series for Criterion, “Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project.”) Once the motor-mouthed bad boy of the New Hollywood generation, Scorsese has improbably evolved into his medium’s elder statesman, and a controversial one at that, earning the fury of the fanboys with his 2019 comment that superhero movies were more like theme parks than cinema. (An eloquent follow-up defense in the New York Times only fanned the flames.)

Whether you agree with him or disagree – the Watch List stands with the maestro – it’s impossible to dismiss his impact on American cinema or the authoritative yet avuncular manner in which he presides over pop culture. There are plenty of filmmakers recognizable from their last names alone. Tarantino. Spielberg. Hitchcock. Marty’s the only one with whom we’re on a first-name basis.

And there’s the filmography: 25 feature films – the 26th, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” will likely premiere at next year’s Cannes – and 16 documentaries, among the latter the achingly fine 1995 epic “A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐, available for streaming only through the public library/university platform Kanopy).

The canard that Marty only makes gangster films is easy to disprove. In fact, only six items on the list could legitimately be called mob movies: “Mean Streets” (1973), “Goodfellas” (1990), “Casino” (1995), “Gangs of New York” (2002), “The Departed” (2006), and “The Irishman” (2019). Others are crime-adjacent: “Taxi Driver” (1976), “Raging Bull” (1980), “Cape Fear” (1991), and “The Wolf of Wall Street” (2013). But there are also comedies (“After Hours,” 1985), dramas about men (“The Color of Money,” 1986) and women (“Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,” 1974), period films (“The Age of Innocence,” 1993), biopics (“The Aviator,” 2004), thrillers (“Shutter Island,” 2010), and family films (“Hugo,” 2011), that last doubling as a love letter to Marty’s chosen medium.

Finally, there’s the trilogy of films that express their maker’s complex relationship to God and which stand among the few genuinely spiritual works of recent cinema: “The Last Temptation of Christ” (1988), “Kundun” (1997), and the majestic, little-seen “Silence” (2016). All in all, a most catholic, and occasionally Catholic, filmography. Celebrate St. Marty’s Day by watching one of the ones you’ve never seen before – or revisiting one of the classics.

Do you have a favorite Martin Scorsese movie? An under-acknowledged gem? Or maybe an overpraised misfire?

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to pass it along to friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how: