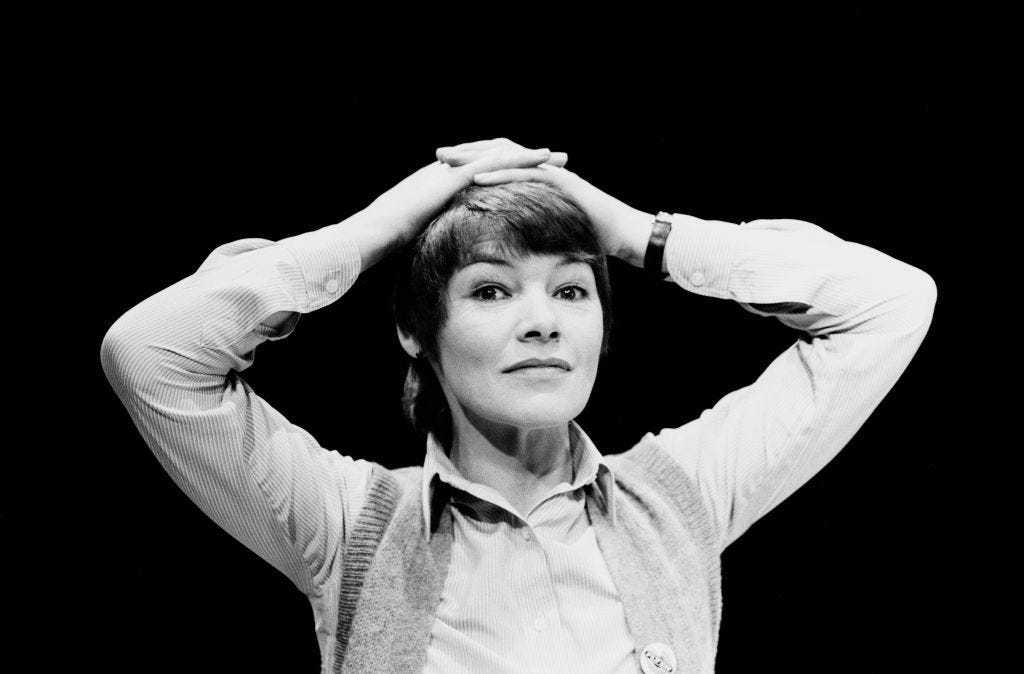

Glenda Jackson 1936-2023

A lion of stage, screen, and Labour politics departs.

Despite her flinty self-possession, Glenda Jackson was surprisingly evanescent as a public person, at least on the American side of the Atlantic. She arrived bewitching Highland cattle and winning an Oscar in Ken Russell’s D.H. Lawrence adaptation “Women in Love” (1969), and it was clear from frame one that there was no one else like her: Imperious, classical, canny, beautiful rather than pretty, so obviously the equal or superior of any man sharing the screen with her that it was never even up for debate.

Those are qualifications for a glittering stage career, which Jackson had – after seeing her in Peter Hall’s 1965 production of “Hamlet,” Penelope Gilliatt presciently wrote “she was the only Ophelia I had ever seen who was capable of playing Hamlet,” and Jackson’s godlike Queen Elizabeth I in the BBC miniseries “Elizabeth R” (1971) made her a household name when it played in the US (and won her an Emmy) on “Masterpiece Theatre” – but they were not what you’d expect in a Hollywood rom-com. Yet after flooring moviegoers in the then-daring “Sunday Bloody Sunday” (1971), there Jackson was winning a second Academy Award in 1973’s “A Touch of Class” opposite George Segal, and for the remainder of the decade she was a top box office draw – a bona fide movie star – in “House Calls” (1978), “Lost and Found” (1979), and “Hopscotch” (1980).

She bounced between film and the stage for much of the 1980s but increasingly devoted her attention to UK politics – Jackson joined the Labour party at 16 and considered herself a lifelong Socialist. In 1990, horrified by the policies of the Thatcher government, she was elected MP for Hampstead and Highgate, and served as a thorn in the sides of John Major, Tony Blair, and others for the next quarter century. No one accused her of being anything other than a devoted and unusually fierce civil servant, but it can fairly be said that an incoming generation of filmgoers completely forgot about her during those years.

It's a shame, then, that Jackson’s return to the stage after her stepping away from politics in 2015 was witnessed only by audiences in London and New York. These were brilliant late-life performances that included a Tony-winning run as one of Edward Albee’s “Three Tall Women” and – fulfilling Gilliatt’s prophecy, or at least proving her point –a “King Lear” that was so titanically royal, so tragically bereft that arguments about gender and representation seemed entirely beside the point.

I was lucky enough to see that “Lear” in 2019 and luckier still to interview Jackson during the play’s run for a Boston Globe feature. When the news came this morning that the actress had died after a brief illness at 87, I revisited the interview transcript and my notes, because if you’re lucky enough to spend time with Glenda Jackson, you want to savor the memory.

On a rainy Manhattan Sunday, she is holding court at a diner on the Upper East Side, exuding a sort of Royal Dramatic force field that keeps waiters, intruders, distant chatter at bay. She is rumored, like Lear, to not suffer fools gladly, but her manner this morning is hearty and bluff, occasionally dismissive in a way appropriate to her status and not at all bothersome. Her voice is a cultivated, agreeable growl. She has a tendency to respond to the question she wants to answer rather than the one she has been asked. An interlocutor doesn’t mind. Respect must be paid.

That was the setting; the conversation covered Shakespeare (his genius, mostly), Brexit (she was appalled), fame (she contentedly noted she was usually unrecognized in the street, although halfway through the interview a fellow diner practically fell on her knees to thank Jackson for, well, everything). At 82, she felt she’d hit the right age to understand Lear, to play him not as a man or a woman but a monarch in his final years, when gender starts to blur. From the transcript:

“The thing that stuck with me when I was a member of Parliament, it was part of my responsibilities to visit old people’s homes, nursing homes, day centers, things of that nature. And what I found was really fascinating, and I hadn’t been aware of it before, as we get older the kind of absolute barriers that define gender begin to fray. They begin to get smoky. You should think about it: When we first come into the world, there is the process that teaches us what our genders are. And at the other end of the age scale, they begin to fracture. I found that quite useful.”

On her Hollywood years:

“It’s like a set waiting to be struck, Los Angeles. And you can’t walk anywhere, which is a big thing with me, because the police stop you and ask you what you’re doing. I was really impressed with the standard of work. I mean, we were doing ‘House Calls’ – was it ‘House Calls’? I think it was ‘House Calls’ – and it was a scene outside. And I said to somebody, well, where’s the generator, how are they going to film this? At which point, a man walked past me, bent down, lifted the grass and plugged something in. Can you believe it? I couldn’t. My God.”

On her movies:

“I must be honest here – I see myself on film, and my viewing is utterly subjective. I look at myself and I think, Why the fuck did you decide to do that? It’s too late, you can’t change it. (laughs) You’re stuck with it.”

When I ask if she had a mentor in her early theater days:

“It doesn’t work like that. Come on! I mean, think: It’s a vastly overcrowded profession, right? And it’s even more overcrowded if you’re a woman. And so one of the primary things when you start is to have a job at all. And it doesn’t matter what it is as long as it’s a job. (laughs) We were bitching last night at the prospect of doing “King Lear” eight times a week, and I said to the guys, ‘Remember the years we spent trying to find bloody work, and we moan about it now.’ Come on.”

And finally, on being asked where she keeps her Oscars:

“One is upstairs in the attic. And one of my nephews, who is now a father himself, asked if he could borrow one for something they are doing at his school. I think it’s in his garage, it hasn’t come back anyway. But my mother, who had all my awards and kept them on the sideboard in the front room, she used to polish them within an inch of their life, and the gold comes off very easily and it’s base metal underneath.

I think that’s a very good allegory.”

Pour one out for a protean player and a grande dame — an actor who always knew who she was but never, ever stopped questing — and maybe seek out “Women in Love” or “Sunday Bloody Sunday” tonight.

What are your memories of Glenda Jackson — your favorite roles, scenes that are burned into your brain? Don’t hesitate to weigh in.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, feel free to pass it along to others.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be very grateful — here’s how.