Forgotten Auteurs: Alan Rudolph

The director of swooning hothouse noirs deserves a revisit.

Maybe it’s a hazard of the trade or maybe it’s just impossible to stay on top of 120 years of film history without dropping a stitch, but I realized the other day I’d forgotten all about Alan Rudolph. Granted, the man has made only one film in the last two decades, but he was a fixture and a fixation of my moviegoing life in the mid-to-late 1980s, and he remains a welcome Hollywood fluke – a director who learned serendipity at the knee of his mentor, Robert Altman, and ran with it in his own distinct direction.

I was reminded of Rudolph the other week, when a young movie fanatic of my acquaintance emailed me to ask if I’d ever seen “Remember My Name” (1978, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐), which he’d recently stumbled across and about which he was still in a fugue state of awed discovery. I allowed that I had seen it – 45 years ago (!) – and retained little but the lingering chill from Geraldine Chaplin’s performance as an ex-con out to settle scores with her former husband (Anthony Perkins). A quick dip into YouTube unearthed the following scene that reminded me of how extraordinary Chaplin actually is in this movie – how genuinely, dangerously spooky – and had me thinking about the wayward career of the man who made it.

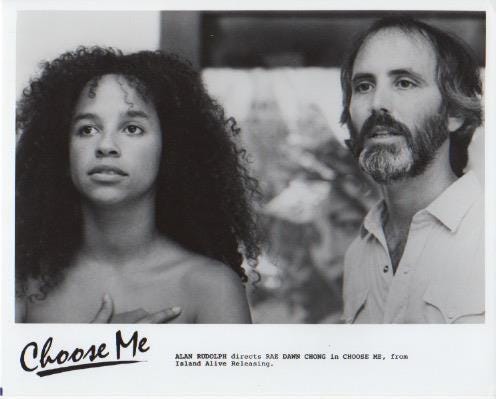

Rudolph’s first real film as writer-director – after a couple of horror Bs, an apprenticeship on “The Brady Bunch,” and a stint assistant-directing Altman during the miracle run of “The Long Goodbye” (1973), “California Split” (1974), and “Nashville” (1975) – was “Welcome to L.A.” (1976, ⭐ ⭐ 1/2, streaming on Tubi), a crowded romantic whimsy that was panned as Altman Lite at the time, but which has a moonstruck vibe that would soon be apparent as a Rudolph trademark. The real breakthrough was 1984’s “Choose Me” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2), in which the sexual round-robin is winnowed down to a manageable number of characters and the songs by Teddy Pendergrass give the whole thing a satiny erotic glow – it’s one of the the most elegantly horny movies of its era. All this plus swoony performances from Keith Carradine, Lesley Anne Warren, and Rae Dawn Chong, and Genevieve Bujold going fascinatingly out on a limb of weirdness. Critics and audiences alike were charmed, and the movie remains the best entry point for Rudolph newcomers – too bad it’s streaming only in an iffy print on the Roku Channel with ads. (Watch it anyway.)

Not surprisingly, the director took the plaudits and his new-found Hollywood credibility and made the most outré film of his career. The fairy-tale noir “Trouble In Mind” (1985, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐, for rent on Amazon and streaming elsewhere) casts Carradine, Bujold, Kris Kristofferson, Lori Singer, and Divine (in his only non-drag role if you don’t count the scene in “Female Trouble” where he has sex with him/herself) in an achingly romantic day-after-yesterday detective story held together by Carradine’s increasingly nutty hairdos, Mark Isham’s glorious score, and Marianne Faithfull’s ravaged vocals. The critics liked it, but it burned up all of Rudolph’s cred.

The journey grew more convoluted after that, with stops in post-WWI expatriate Paris (“The Moderns,” 1988, ⭐ ⭐, not available on VOD) and at the Algonquin Round Table (“Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle,” 1994, ⭐ ⭐ 1/2, for rent on Amazon and AppleTV), the occasional major studio thriller (“Mortal Thoughts,” 1991, ⭐ ⭐ 1/2, for rent on Amazon, AppleTV, YouTube), and a handful of wonky, lovingly acted, and sometimes successful comedy-dramas that can only be called Rudolph-esque: “Love At Large” (1990, ⭐ ⭐, streaming on Tubi), “Equinox” (1992, ⭐ ⭐ 1/2, for rent on AppleTV), “Afterglow” (1997, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐, with a best actress Oscar nomination for Julie Christie, widely available). The Kurt Vonnegut adaptation “Breakfast of Champions” (1999, ⭐ 1/2, unavailable on VOD) and the comic thriller “Trixie” (2000, unavailable on VOD) received some of the director’s worst reviews, but “The Secret Lives of Dentists” (2002, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2, sadly unavailable on VOD), from a Jane Smiley novella with a script by Craig Lucas (“Prelude To A Kiss”), is one of the best unknown films of the new century – a deliciously bittersweet comedy about married dentists (Campbell Scott and Hope Davis), small-town opera productions, infidelity, paranoia, and the bacterial petri dish that comes with being the parents of small children.*

“Dentists” was either a return to form or a last gasp. Rudolph has made only one film since then, a 2017 romance called “Ray Meets Helen,” which I haven’t seen – I intend to remedy that soon – but it sounds very much like an Alan Rudolph movie with even less plot and more pheremones than usual. Which, honestly, is what the man has been working his way toward all along: Love’s drunken intoxication put onto film with as few filters or distractions as possible. He’s 79 now, at last report happily squirreled away with his wife on Bainbridge Island in Washington State, and it’s likely this is the last we’ll see from him. You could do worse than circle back and start at, or near, the beginning: “Remember My Name,” the movie that astonished my young friend, or “Choose Me,” a film that once enraptured us all.

* ”The Secret Lives of Dentists” is so forgotten that my 2003 review for the Boston Globe has vanished from the digital ether. I self-indulgently reprint it here only because I recall it as a review I enjoyed writing as much as I enjoyed the movie (it doesn’t always work out that way) and to give you a sense of the film’s embattled, idiosyncratic charms. As noted above, the film’s unavailable for streaming, but my library has the DVD, and so might yours.

“’Dentists’ is a Biting Look at Family”

(originally published in The Boston Globe on August 8, 2003)

If you're a singleton, you may stumble out of "The Secret Lives of Dentists" in a heightened state of annoyance. Who are these people, you may ask, and why on earth would I care about them?

If you're married with children, you may find yourself paralyzed with horror, hilarity, and recognition. "Dentists" may not be the best movie ever made about the perils of family life, but it is among the most ruthlessly comic.

Campbell Scott and Hope Davis play married dentists David and Dana Hurst. They have a lovely home in Westchester, a thriving practice, and three beautiful young daughters: all seems well. But David's natty moustache bristles with disappointment, and Dana no longer looks at him with desire but with regret. She sings in a community opera company, and we and he sense that this is where she has placed whatever remains of her dreams. "I could sing every night," Dana says mournfully, and maybe she intends to: visiting backstage, David stumbles upon what may be evidence of his wife's unfaithfulness.

That possible infidelity nags at him like a toothache, and teeth, David assures us, "last forever." But he’s a good husband and a good father -- even to toddler Leah (Cassidy Hinkle), who clings to Daddy like a barnacle and belts Dana whenever she passes by -- and he intends to keep this marriage on track if it kills him.

Very nearly does. David is not much of a people person -- "the social nature of the dental business is the hardest thing for me," he admits. To cope with the steamkettle stress, he internalizes his worst patient, a bilious trumpet player named Slater (Denis Leary), and turns him into the devil on his shoulder. This inner Slater – visible only to us as he leans darkly against the kitchen island – stokes David's fury and feeds him vicious comebacks that he passes on to wife and children. To the outside world, the dentist is veering toward meltdown. To the audience, Leary is a lively gimmick who fairly quickly wears out his welcome.

He's also the only sign that this is an Alan Rudolph movie. The director started his career three decades ago as a Robert Altman camp follower, and his subsequent films have been moonstruck romances ("Choose Me," "Afterglow") or whimsical duds ("The Moderns," "Trixie"). Rudolph usually writes his own screenplays, but here he's working from a script by playwright Craig Lucas that's based on a novella by Jane Smiley. Both writers are rather more tough-minded than the director, and it shows.

Is David's anger making his children sick? There are mysterious stomachaches, and eventually the abyss between the couple grows so deep that father takes his girls out to the country house, where everyone promptly comes down with the flu. The second half of "Dentists" is a masterful worst-case scenario of black family comedy, with all the Hursts falling prey to tag-team vomiting, hallucinations, despair, and truth-telling. It's hard to be repressed when you're crouched over a toilet.

Maybe this is the worst date movie ever devised by mortal man, but it's terribly funny -- emphasis on both words -- to anyone who has suffered the slings and spit-ups of raising small children. Exquisitely acted by Scott and Davis, "Dentists" is bleakly attuned to the bittersweet nuances of matrimony – to the way you can sometimes know someone less the longer you live with them. “I thought marriage would be like Cinerama,” says David. “It would get wider and wider. It doesn’t. It gets smaller and smaller.” There’s a cavity there, and it’s not the kind you can find on an X-ray.

Thoughts? Don’t hesitate to weigh in.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to pass it along to friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the management would be very grateful — here’s how.