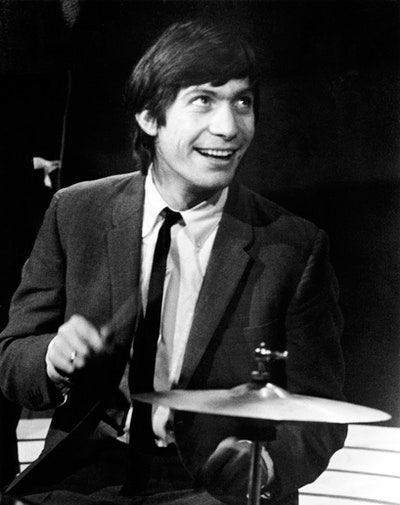

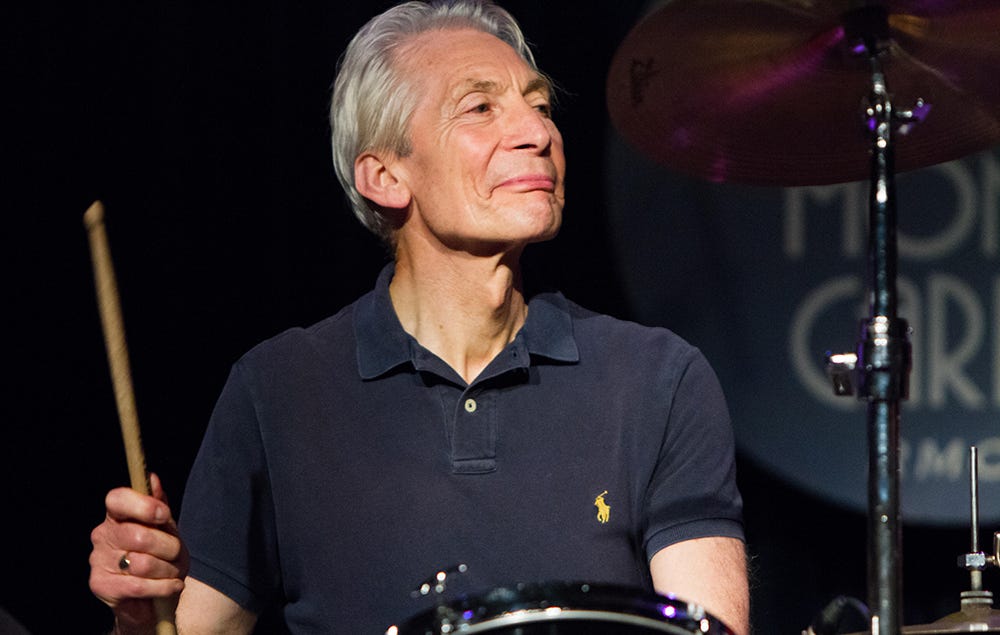

Charlie Watts 1941-2021

The Rolling Stones drummer was an invisible anchor for his group and his times.

Ah, damn it, Charlie Watts has died. The moment I heard the news today – on vacation on the Cape, sun streaming in the window, a pot of New England baked beans in the oven – I stopped what I was doing and put on “Street Fighting Man,” from 1968’s “Beggar’s Banquet.” The opening of the song is absolutely electrifying and the irony is that it’s all acoustic, Keith’s guitar coming in with a furiously strummed ker-RANGGGG for two bars and then Charlie’s bass drum beat an implacable call to arms, crashing in on the downbeat like a syncopated battering ram: BAM… BAM… BAM… BAM-BAM-BAM.

It’s one of the most exhilarating sounds I’ve ever heard.

The song came out in late 1968 but was recorded in April and May of that year. The Summer of Love was over; the lyrics addressed the necessity and futility and necessity of rising up in open rebellion against a corrupt political system. Or maybe it was just about blowing off steam with a rumble. It’s the Stones, you were meant to argue with it. But Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in April of that year, and the riots following his assassination may have given further fuel to the ambiguities of “Street Fighting Man.” It’s a song that purposefully teeters on the edge of complete chaos and the only thing keeping it from exploding in your face is the angry, steady heartbeat of Charlie Watts’ bass drum.

He was an odd man out, in his band and in his era. A taciturn jazz percussionist in a group of anarchic rockers. A poker face at the back of the drum kit while Mick was licking his cartoon lips and yowling like a stray cat. The legendary drummers of the Classic Rock era functioned as their bandmates’ Id: Keith Moon driving cars into swimming pools, John Bonham the hard-drinking Beast of Led Zeppelin, Cream’s Ginger Baker so terrifying that a 2013 documentary about his life is titled “Beware of Mr. Baker.” Even dear, lovable Ringo was a superstar on the strength of his nose and his wide-eyed innocence. By contrast, Charlie Watts was the cipher that drove the Rolling Stones. The man wore suits, for pity’s sake. In the 1960s. (Vanity Fair elected him to the International Best Dressed Hall of Fame in 2006.)

He was older by a year or two than Mick and Keith and Brian Jones (although not as old as original Stones bassist Bill Wyman, who was already pushing 30 when the group broke through in the mid-1960s.) But he seemed somehow parental to the rest of the group, or maybe a protective older brother, the human metronome keeping the pulse of the enterprise steady while the others set off cultural bombs on the main stage and on the periphery. No 15-minute drum solos for Charlie Watts. He had better things to do. Even his fills were essays in inventiveness and tact.

It’s instructive to listen to a classic rock album that you’ve long had tattooed on your memory and for once pay strict attention to the drumming. With Ringo, it’s an education in the importance of the basics. With Keith Moon, it’s downright exhausting. To listen to Watts’ drumming on the run of albums that remains the Rolling Stones’ best work (by far), from “Aftermath“ (1966) to “Exile on Main Street” (1972), is to listen to a playful, subtle sensibility that knows when to go hard but always – always – serves the song. The volleys of angry rat-a-tats that push “Get Off Of My Cloud” forward; the whirling-dervish beats that propel “Paint It, Black.” The martial snare drums that march the singer of “Take It or Leave It” to his execution.

Take “Factory Girl,” the penultimate track on “Beggars Banquet.” Coming two songs after “Stray Cat Blues,” Mick and Keith’s intentionally incendiary ode to statutory rape, “Factory Girl” is sweetly comic, sung from the POV of a guy waiting outside a manufacturing plant for his girlfriend to get out of work. It’s Mick doing his working-class-prole schtick with a honeyed “Southern” drawl but the details are pungent – “Waitin’ for a girl, and her knees are much too fat/Waitin’ for a girl, she wears scarves instead of hats/Her zip’s broke down the back” – and what on earth is Charlie Watts doing? He’s playing the Hindustani hand drums known as the tabla but with sticks, an effect that imparts to the song a clattery warmth that feels both down-home and universal. It’s what makes the song funny and moving instead of a pose.

Or the monumental “Loving Cup,” from “Exile”: After nearly a minute of Nicky Hopkins’ piano, producer Jimmy Miller’s maracas, Richards’ acoustic guitar and Jagger’s vocals, Watts arrives at the first chorus to take a roaring lap around the drum kit and kick the whole thing into high gear, slowly goosing the song’s forward momentum until by the final choruses the band and the listener alike are dancing joyfully along the edge of the abyss. As a jazz mind in a rock and roll context, Watts could swing so hard it hurt.

He survived throat cancer in 2004. Earlier this month, it was announced that, due to an unspecified medical procedure, Watts would not be joining the Stones for their upcoming No Filter tour. He died in hospital early today, August 24, surrounded by his family; no further details are available at this time.

The first thing I did when I heard he was gone was put on “Street Fighting Man” and play that opening riff as loud as is humanly possible.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

Or subscribe. Thank you!